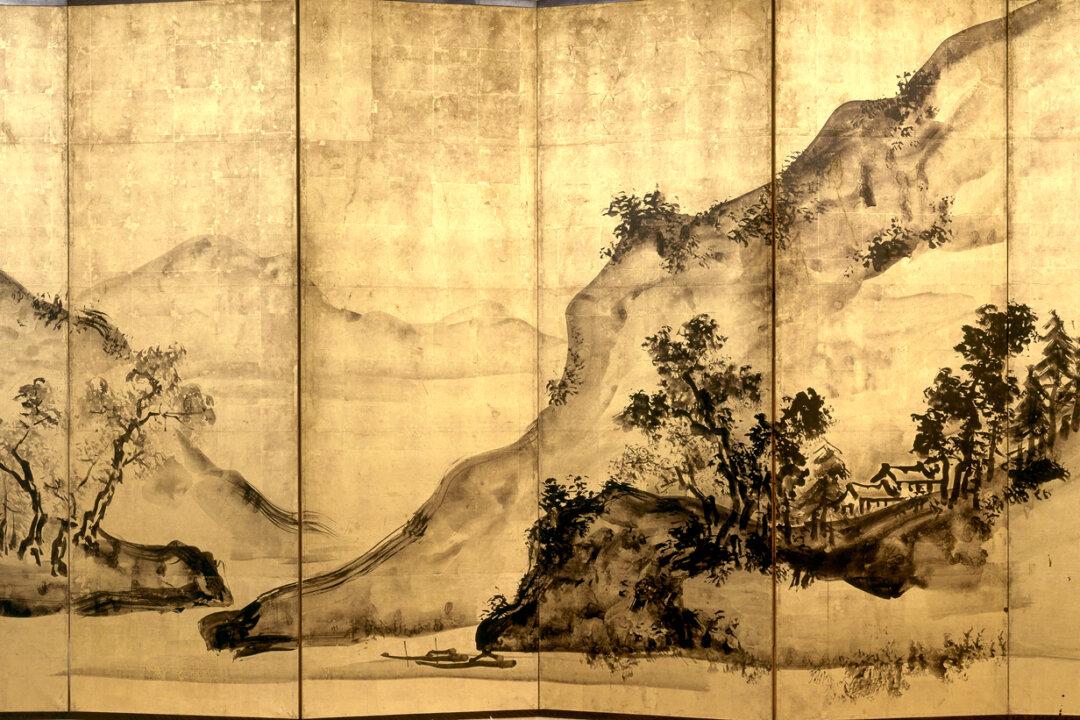

Picture Japan’s rich history and tradition as Princeton University Art Museum invites you to explore Japan’s heritage through the exhibition “Picturing Place in Japan,” which is on display until Feb., 24. The exhibition is a chance “to engage with one of the most central traditions within the history of Japanese art,” says James Steward, director of Princeton University Art Museum, on the TownTopics website.

Through book illustrations, woodblock prints, paintings, and photographs, nearly 40 artworks from the 16th century to the 21st century explore the different ways that place, imagined or actual, is found in Japanese art.