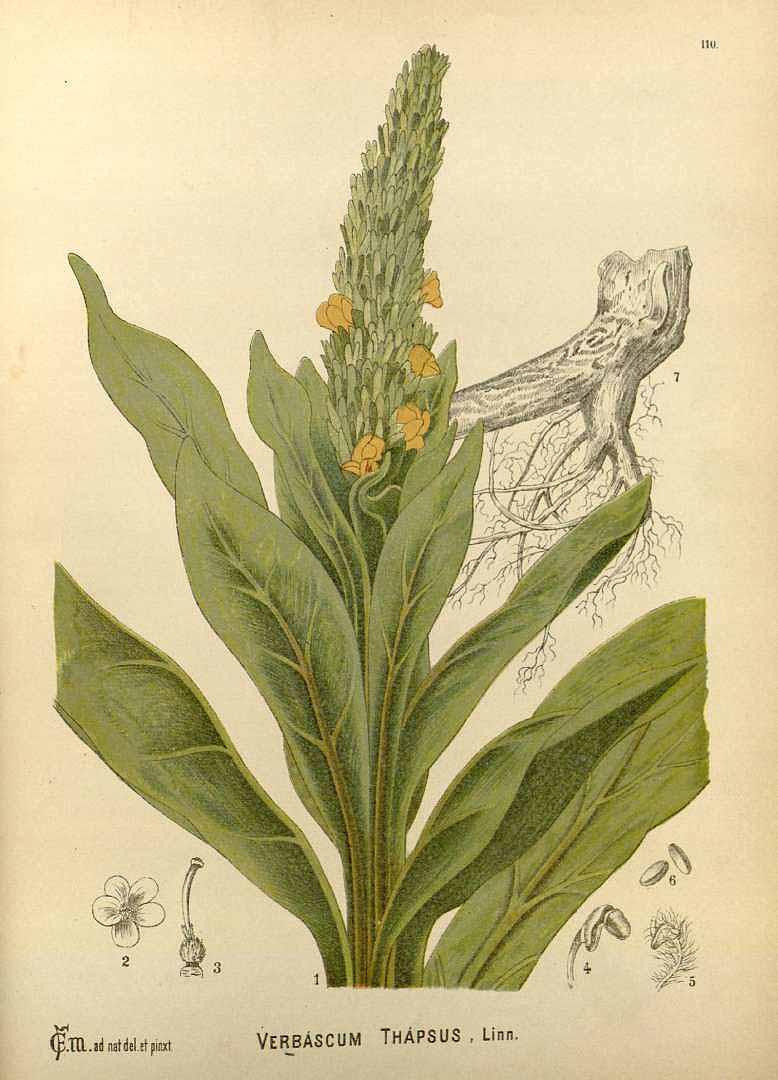

Mullein is a common roadside weed that really stands out in a crowd. The large leaves feel like thick wool flannel. In its second year, the plant sprouts a stalk that can grow six- to eight-feet high.

Mullein has remained a favorite herb in European folk medicine for centuries, and was quickly adopted by Native Americans when it came to the New World.

Today, it is primarily used as a cough remedy, but it has other medicinal uses that are often overlooked—some were only recently discovered.

Bone Deep Cough

Mullein tea can be used for all types of coughs, but it is particularly suited for deep, dry coughs that cause pain in the chest.

But, mullein is much more than a cough remedy, according to Matthew Wood, a registered herbalist and author of several books on herbal medicine. In “The Book of Herbal Wisdom,” Wood recalls when he recommended mullein to a friend after she fell against a two-by-four and cracked a rib.