Profuse sweating, a runny nose, and a GI tract that feels like it’s on fire: These sound like symptoms of an illness, but they are also a typical reaction to eating a hot pepper.

An estimated one in four people around the world eat hot peppers every day. Why is a food that causes pain and suffering so popular? When you consider all the health benefits of hot peppers, it’s easy to see.

Chilies (or as the Aztecs called them, “xillis”) originate from warm regions of the Americas. Chilies have been eaten there since at least 7,000 B.C. and remain a fundamental part of Mexican, Central American, and South American diets.

It was Columbus who first called them peppers. He mistakenly guessed the chili plant was related to the hottest herb then known in the Old World, the peppercorn.

Chilies are actually part of the nightshade family of plants, but unlike other New World nightshades, such as tomatoes and potatoes, peppers were embraced in some European regions right away because they offered a cheaper and hotter alternative to the pricey peppercorn.

Chilies soon spread to Asia, Africa, and other tropical regions where they became even more popular. It’s hard to imagine what Indian, Thai, or Szechuan cuisine would be like today without this spicy foreign fruit.

Spice of Life

Chilies are an easy and economical way to bring pizzazz to otherwise bland food. But there may also be practical reasons why peppers were so readily adopted into traditional diets. According to a 1998 report from Cornell University biologists, the main reason cultures cultivated hot peppers was “to kill food-borne bacteria and fungi.”

Before refrigeration, spoiled food could easily lead to illness and death, particularly in tropical regions. Adding antimicrobial chilies helped fend off the health dangers of ingesting bacteria-tainted food. Peppers not only give meals more exciting flavor, but they also make them safer to eat.

Studies show that peppers can minimize the effect of food-borne pathogens, such as listeria, salmonella, and other strains of harmful bacteria and fungi. Other research finds that capsaicin, the chemical that makes chilies hot, may also combat cancer cells.

[aolvideo src=“http://pshared.5min.com/Scripts/PlayerSeed.js?sid=1759&width=580&height=350&playList=518102458&responsive=false&pgType=console&pgTypeId=editVideo-overviewTab-copyCodeBtn”]

Pain and Heat

The botanical name for chili peppers is Capsicum. Both this name and capsaicin comes from a Greek word which means “to bite.” Hot peppers are the food that bites you back.

Capsaicin is an odorless, oily alkaloid found primarily in the membrane that holds the pepper seeds inside the fruit. Any body part that comes in contact with capsaicin will experience a cruel sting that can last for a few seconds to a few days. Mucosal tissue is especially sensitive to this chemical—ask anyone who has accidentally rubbed their eyes after chopping jalapenos.

[pullquote author="“ org=”"]From poblano to cayenne to habanero, the heat intensity of peppers vary widely.[/pullquote]

From poblano to cayenne to habanero, the heat intensity of peppers vary widely. In 1912, pharmacist Wilbur Scoville developed a metric to measure chili hotness. Scoville’s system describes how many cups of water it would take to dilute an extract of a particular pepper until heat can no longer be detected on the human tongue. For example, a mild bell pepper ranks a zero—no dilution necessary. Jalapenos can range between 5,000 and 15,000 SHU (Scoville Heat Units). A cayenne pepper can reach 100,000 SHU.

Peppers have only grown hotter with time, and every few years a new record-breaking variety emerges. Not long ago, the Bhut Jolokia (AKA the ghost pepper) was the reigning chili champion with over one million SHU, but it lost its title to the Trinadad Scorpion, which ranks two million SHU—as hot as civilian grade pepper spray.

In 2014, the “Guinness Book of World Records” awarded “world’s hottest” to the Carolina Reaper with some specimens measuring 2.2 million SHU.

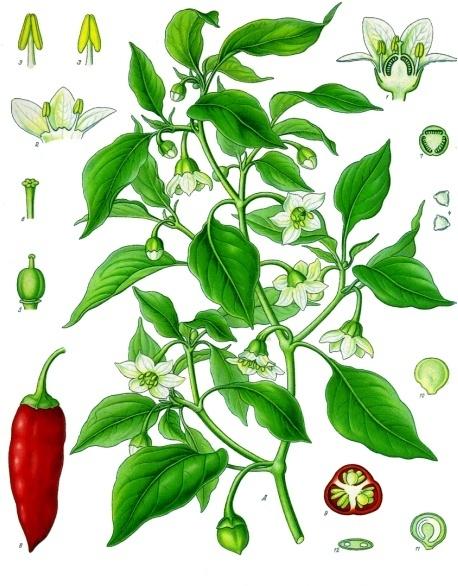

[caption id="“ align=”alignnone“ width=”458"] Botanical illustration of cayenne pepper by Franz Eugen Köhler. (Public Domain)[/caption]

Botanical illustration of cayenne pepper by Franz Eugen Köhler. (Public Domain)[/caption]For something that causes so much pain, peppers are surprisingly safe. One study found that it would take eating three pounds of the world’s hottest chilies to kill a person. Given that most people can barely choke down a single chili without great drama, a pepper fatality is highly unlikely.

In fact, capsaicin has many positive effects on the body, and can even used to treat chronic pain. Commission E—the agency that regulates botanical medicine in Germany—approves cayenne pepper as a topical ointment for muscle spasms. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves creams containing .025 percent capsaicin for arthritis. Some studies have shown that capsaicin may also be effective for cluster headaches.

It sounds counterintuitive to use a pain inducing product to soothe a painful condition, but capsaicin works with the body’s own chemistry to provide relief. A few applications of capsaicin cream exhausts the body’s supply of pain signaling neurotransmitters until the sensation of pain eventually fades. However, until this happens, the cream will burn.

The really concentrated capsaicin creams are only available at the doctor’s office. Using these super spicy creams require an initial application of a topical anesthetic so the patient can tolerate the burn.

Capsaicin also triggers the production of endorphins—feel-good, pain-relieving hormones that come from the pituitary gland in response to pain. Those who can endure the initial agony of eating a really hot pepper may be rewarded with a euphoria that can last for hours.

Digestion

In traditional herbal medicine, chilies are considered a kind of stimulant, and they are often used to wake up a sluggish digestive system. In herbal folk medicine, those suffering from constipation or slow transit time are urged to spice up their meals.

Hot peppers do not, as some believe, harm the lining of the gut wall—although it might feel like it. While stomach ulcers were once thought to be aggravated by hot peppers, new understandings reveal that they can actually help heal them. Research has shown that capsaicin “inhibits acid secretion, stimulates alkali, mucus secretions and particularly gastric mucosal blood flow which help in prevention and healing of ulcers.”

However, for people who already have an overstimulated or irritated digestive system such as IBS, chilies can make symptoms worse.

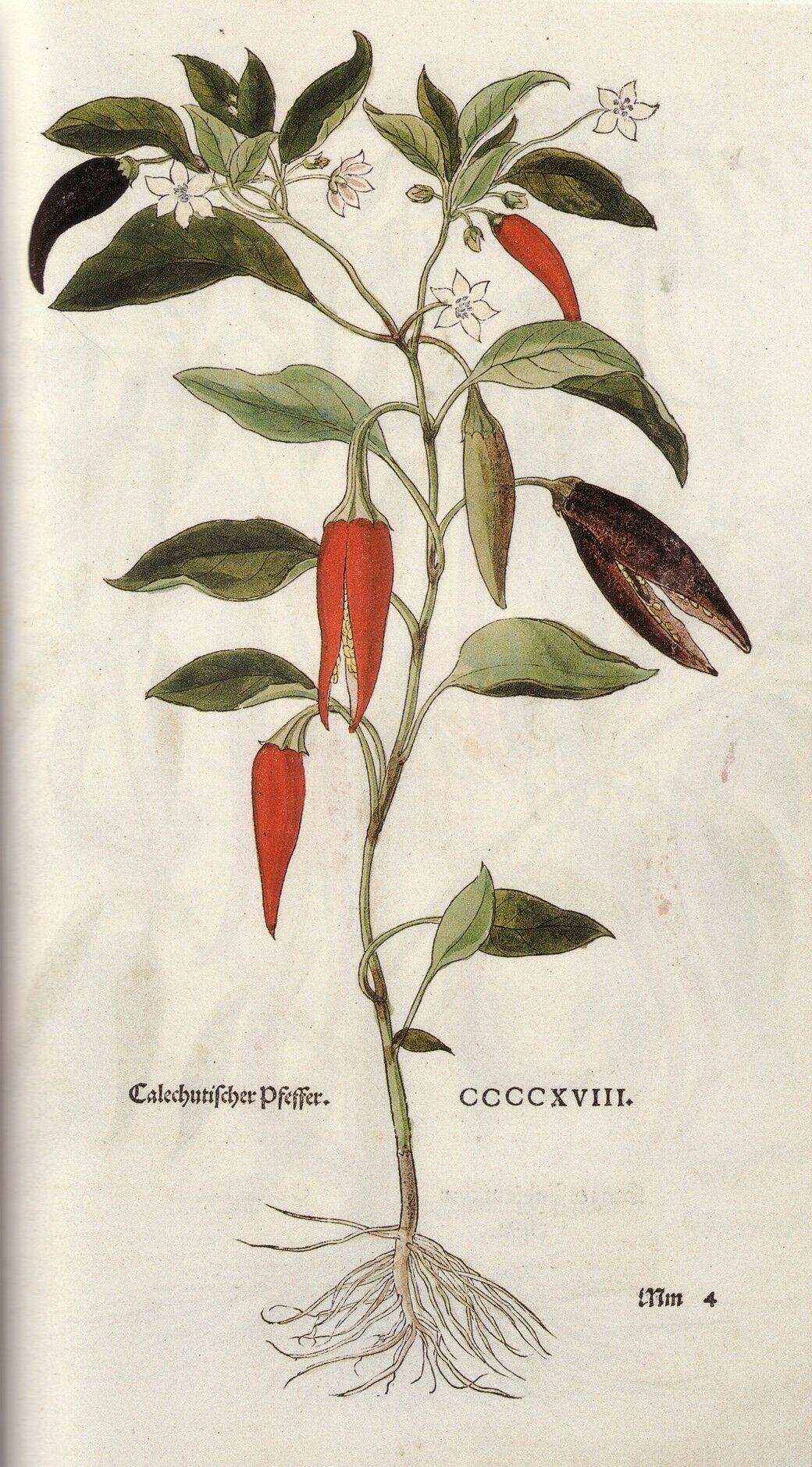

Cayenne pepper illustration by Leonhart Fuchs. (Public Domain)[/caption]

Cayenne pepper illustration by Leonhart Fuchs. (Public Domain)[/caption]Heart Health

Chilies have been a favorite among herbalists for centuries. Hot peppers not only treat a variety of ailments, but when used in formulas they can boost the power of other herbs. Some herbalists throw cayenne into almost every formula because of its amplification power.

One of cayenne’s most ardent admirers was Samuel Thomson, often known as the father of American herbalism. In the early 19th century, when conventional medicine still relied on bloodletting for treating disease, Thomson preached the use of Native American herbs. His top two were lobelia and cayenne.

According to the late 20th century herbalist Dr. John Christopher, cayenne is “one of the greatest herbs of all time.” His personal daily regimen included a spoonful of cayenne pepper powder stirred into a glass of water.

Dr. Christopher believed that cayenne was one of the best remedies for the cardiovascular system and claimed that a strong cup of cayenne tea could even save a person from a heart attack. A 2013 animal study from the journal “Circulation” found that capsaicin ointment rubbed on the skin during a heart attack resulted in an 85 percent reduction in cardiac cell death. The results prompted researchers to recommend the ointment to reduce “the extent and consequences of heart attack.”

Stimulating chilies have also been shown to dilate arteries, regulate blood pressure, improve heart performance, and prevent clots. Sprinkled into a wound, cayenne powder can also stop bleeding usually in under a minute and is typically painless

Cold and Flu

For its antimicrobial action alone, hot peppers are a great addition to cold and flu treatment, but they’re also good for symptomatic relief too. Capsaicin can thin phlegm to relieve stuffy sinuses and loosen congestion in the lungs, and can also cause you to break a sweat to lower a fever.

How to Use

If you want a regular dose to address a particular health problem, cayenne pills or tinctures are reliable forms. But it’s more fun to take your hot peppers with food. In addition to capsaicin, chilies are a great source of vitamins A, B, C, and E, as well as calcium, phosphorus, and iron.

[morearticles]1249486, 1343164, 336161[/morearticles]

There are lots of ways to include capsaicin in your diet: freshly chopped, dried flakes, cayenne powder, chili-infused vinegar, or hot sauce. Homemade hot sauce is fun to make and really easy. Just take salt, vinegar, garlic, and a combination of your favorite peppers (roasted or raw) and throw them into a blender.

How much chili is too much? Only your tongue can tell. Hot pepper tolerance varies a lot from one person to the next, but the more often you eat chilies the more heat you will be able to tolerate.

If a chili experience becomes too intense, don’t reach for water, which only makes the pain worse. Instead try starchy food, like bread, rice, or potatoes. The best remedy is milk. Dairy contains a protein called casein that helps neutralize capsaicin.