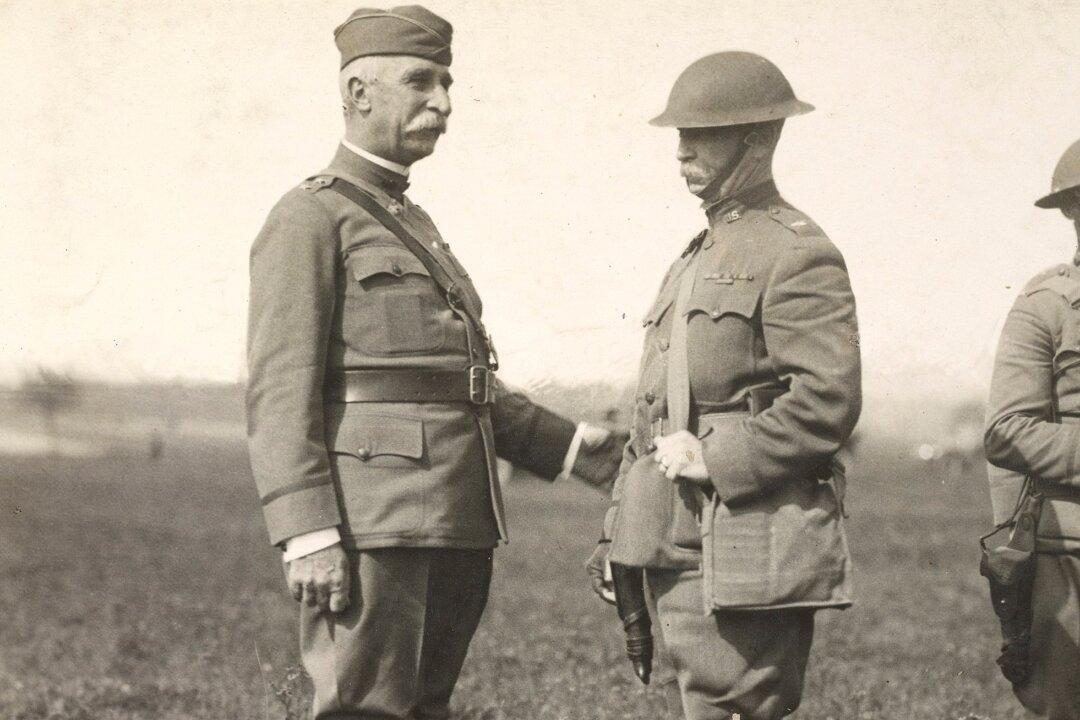

Born shortly before the end of the Civil War, Harry Hill Bandholtz (1864–1925) seemed destined to become a military man inclined toward diplomacy over violence.

At 17, he joined the Illinois National Guard and earned the rank of lance sergeant. He was nominated to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and graduated in 1890. As part of the U.S. Army during peacetime, he spent several years teaching at the Michigan Agricultural College. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, he served as a captain of the 7th Infantry Division. His courageous actions in Cuba earned him a Silver Star (awarded posthumously).