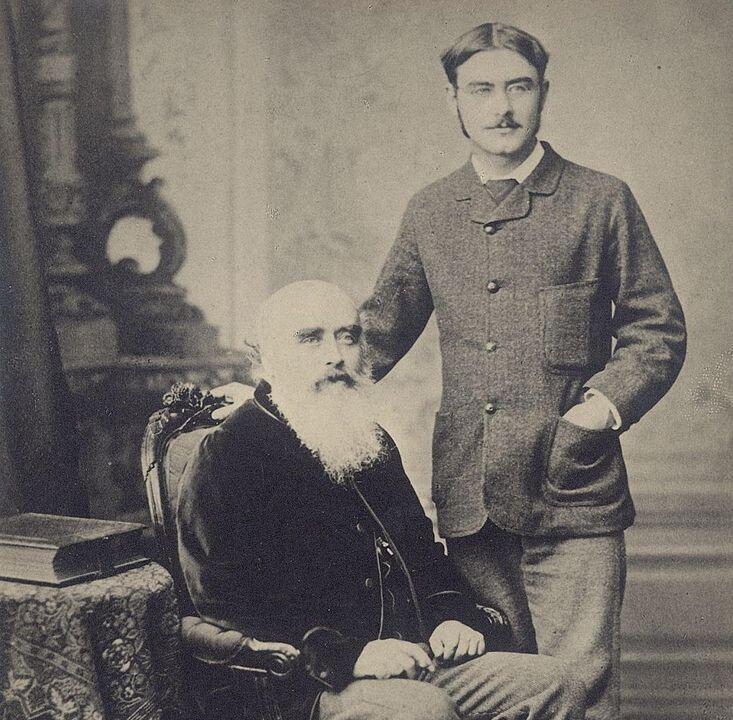

“When I was a boy of fourteen,” Mark Twain once noted, “my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

Like Twain, some children roll their eyes when parents or grandparents offer advice. The 1960s gave birth to the adage “Never trust anyone over 30,” which some young people believed until they hit middle age and found themselves parents or in positions of authority. That’s when the eye rolling abruptly ended.