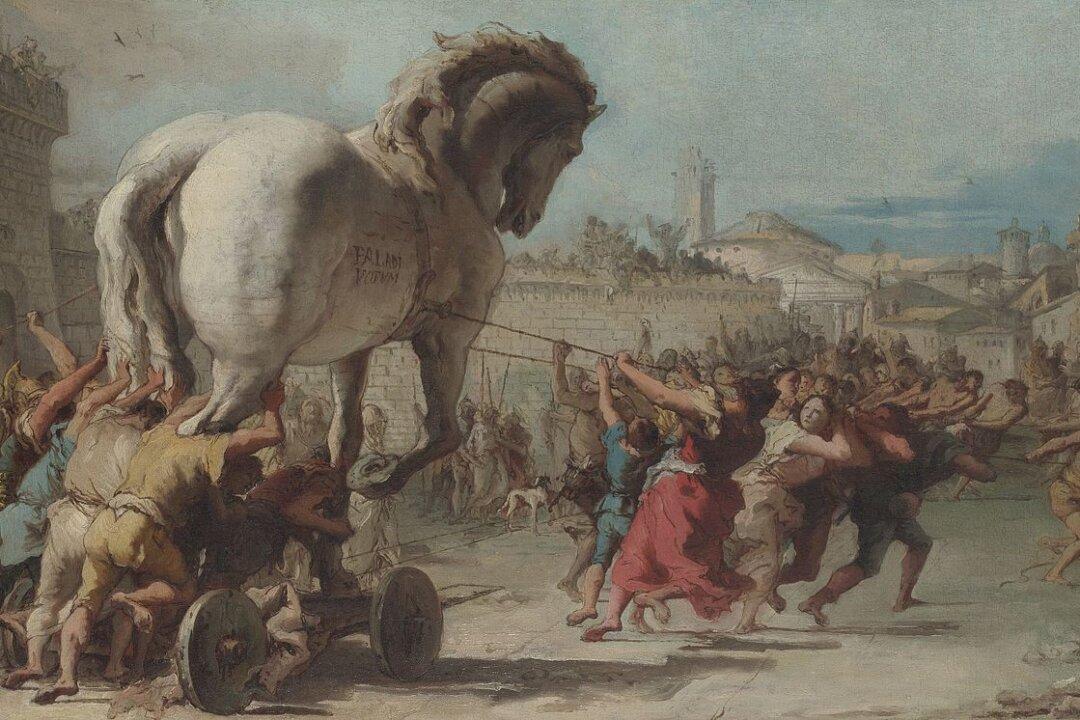

Sometimes, things appear too good to be true. The dangerous and harmful can be masked by promises of beauty and pleasure.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about promises of worldly utopia and how these promises have historically led to bloodshed. Ideologies such as these often give their adherents a sense of superiority grounded in a moral absolutism that refuses any opposing viewpoints, and in so doing, enemies are created out of those who would otherwise be friends.