Matthew Fontaine Maury (1806–1873) was born near Fredericksburg, Virginia, before moving with his family at the age of 5 near Nashville, Tennessee. His brother, John, had fought in the U.S. Navy during the War of 1812 aboard the Essex. Maury was obviously too young to be in the military at the time, and it appeared that his life would be made on the farm. An injury, however, changed the course of his life—as injury would later in life. At the age of 12, he fell 45 feet from a tree and injured his back. No longer cut out to work the farm, he was sent by his father to Harpeth Academy, where he excelled.

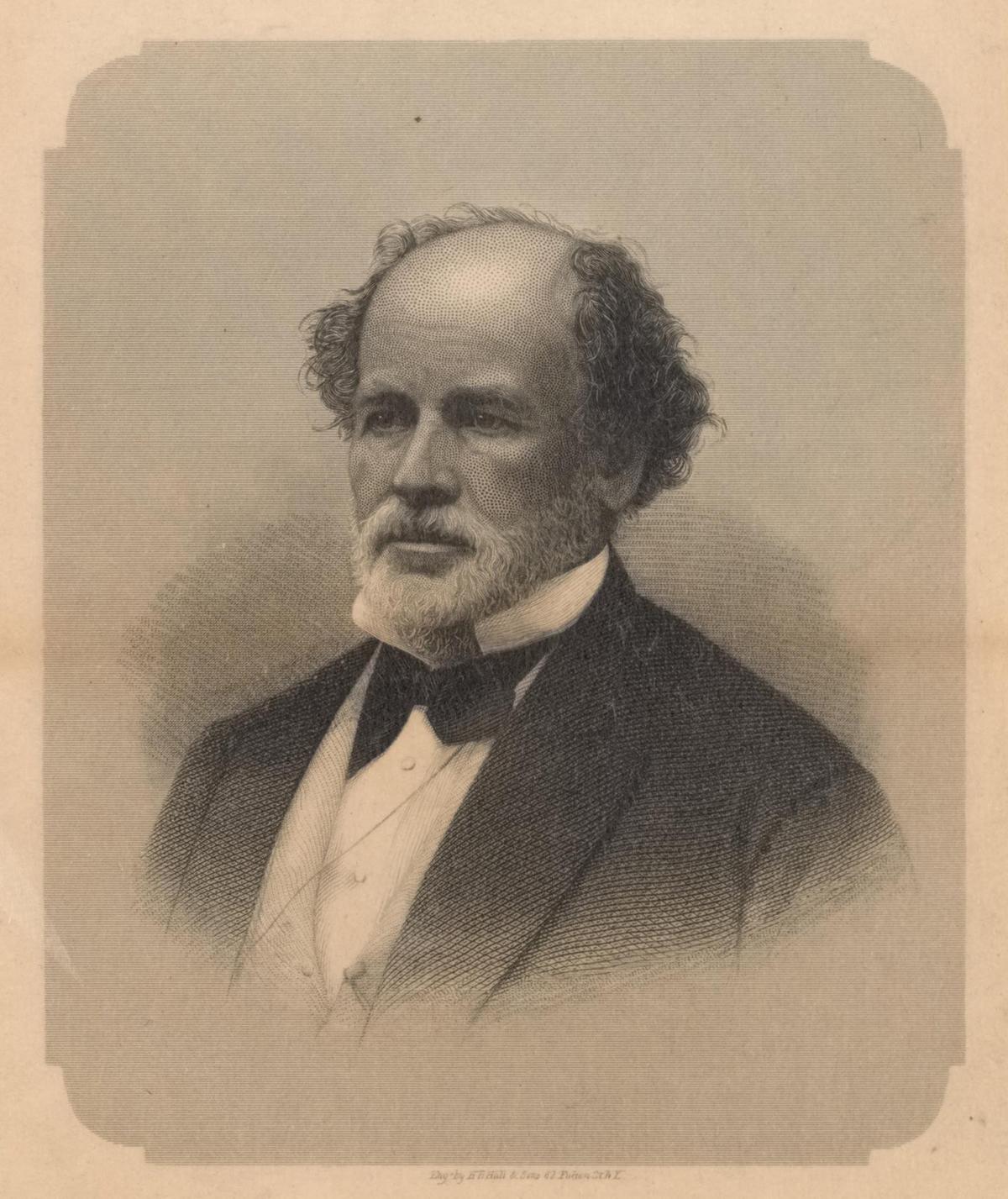

Portrait plate of Matthew Fontaine Maury in the "Matthew Fontaine Maury Papers: General Correspondence," 1825–1839. Library of Congress. Public Domain