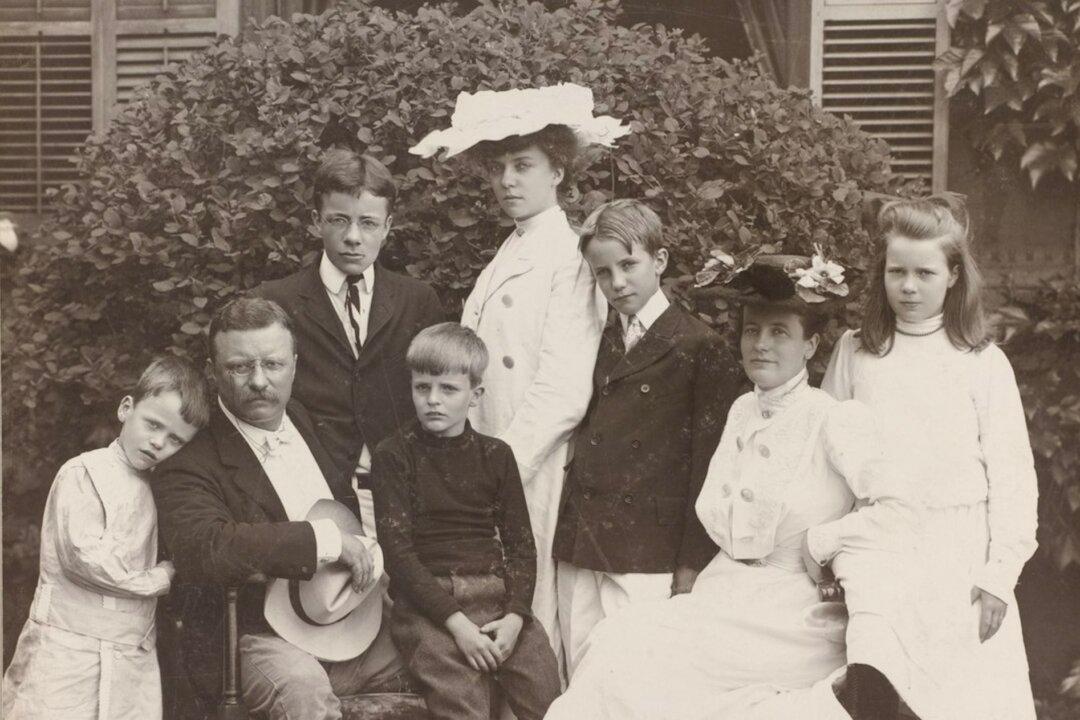

In a matter of two months, Theodore Roosevelt Sr. was dead. Cancer had quickly devoured the father of one of America’s most famous presidents. The son, a 19-year-old eventual executive, was crushed by the loss of his father, a man who was a founder of the American Museum of Natural History and whom the son viewed as “the best, wisest and most loving of men.”

It was Theodore Roosevelt Jr.’s father who had pushed for him “to make his body” in order to combat his sickliness, specifically his asthma. He vowed to do so in order to pursue all that his mind wished to do but his frail body wouldn’t allow. His workout regimens began what he would term “the strenuous life.” “Teedie,” as he was known as a child, was curious about nature, especially birds. Though his childhood body often prevented the strain of even mild adventure, it didn’t stop him from studying and sketching nature’s subjects. At the age of 14, while his family vacationed on the Nile River, he and his father would hunt along the banks, killing, dissecting, preserving, and labeling the specimens.

Roosevelt had the gift of hyper-focus, which allowed him to block out other thoughts and distractions and focus solely on his task at hand. Shortly after his father’s death, his grief could be stifled only by the intellectual demands of his studies at Harvard College. “It has been a most fortunate thing for me that I have had so much to do,” he wrote in his diary. “If I had very much time to think, I believe I should almost go crazy.”