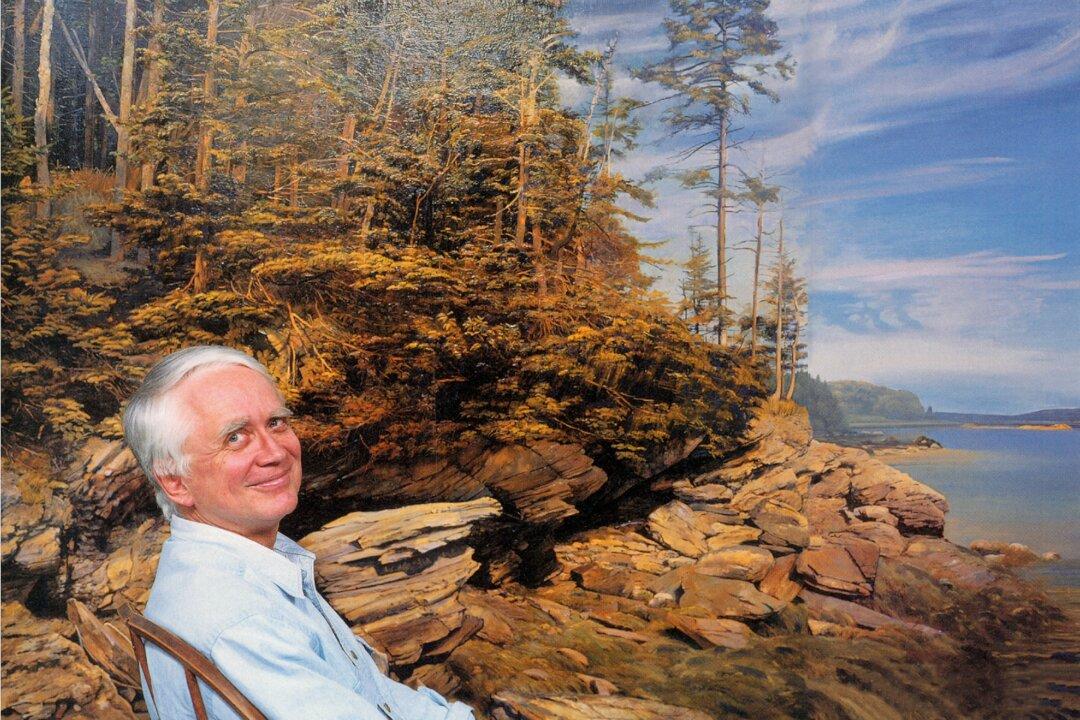

Maine-based realist painter Joel Babb very nearly became an abstract expressionist. But a series of events compelled him to follow past masters—Leonardo da Vinci, Claude Lorrain, and John Ruskin, to name a few—to become the successful artist he is today.

Babb’s work is featured in private collections and in prominent ones, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and Harvard Medical School.