“Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.”

These lines, attributed to actor Edmund Gwenn (Santa in the original “Miracle on 34th Street”), sum up the state of comedy today with one important twist. Given the state of contemporary humor: Dying is easy. Comedy is nonexistent.

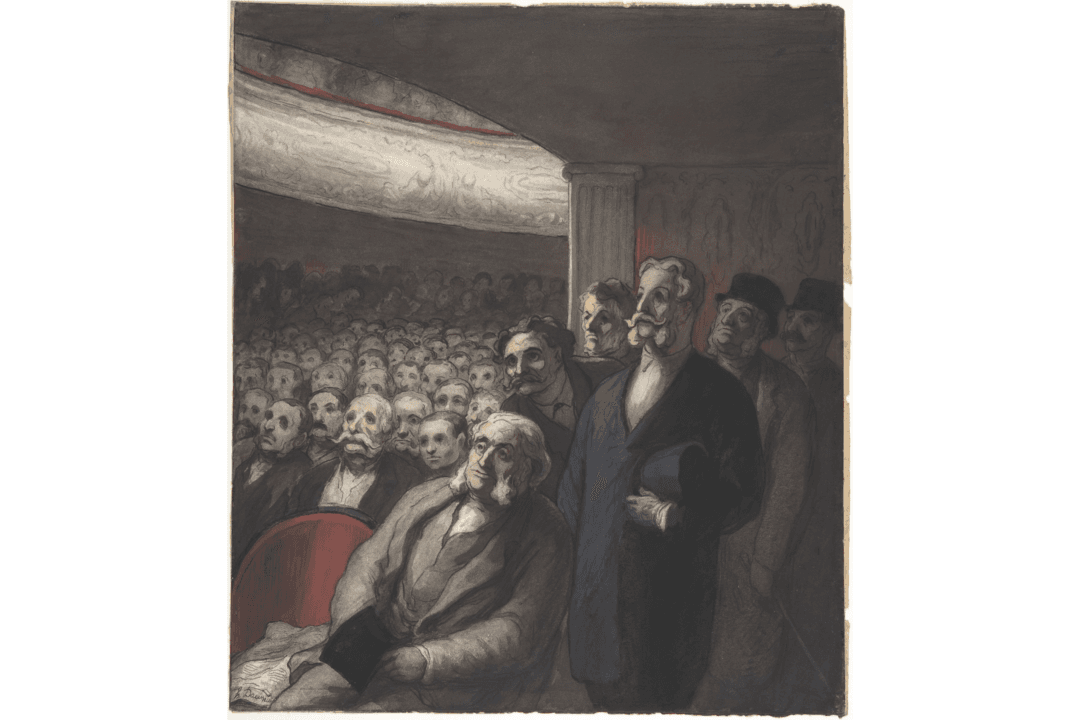

As a culture, we have been instructed not to laugh anymore and definitely not to enjoy ourselves unless we are miserable. So careful are we that we might offend another with even the most innocuous comment, we have become essentially a humorless society, overseen by scolds. The Natural Theater—the antidote to the Theater of Misery—seeks to reintroduce humor into our lives.

In coining the term “Natural Theater,” in addition to restoring humor, I aim to restore protagonists to a state capable of self-reflection and heroism, rather than to one of victimization by oppressors, as “Theater of Misery,” another term I’ve coined, would have it.