A great many Americans know about the confinement of Japanese-American citizens and the camps into which they were interned. Today, it’s considered a stain on American history. What is less well known is what occurred inside the camps. It’s tempting to conclude that the camps were akin to European concentration camps where daily horrors were inflicted upon the internees. They decidedly were not.

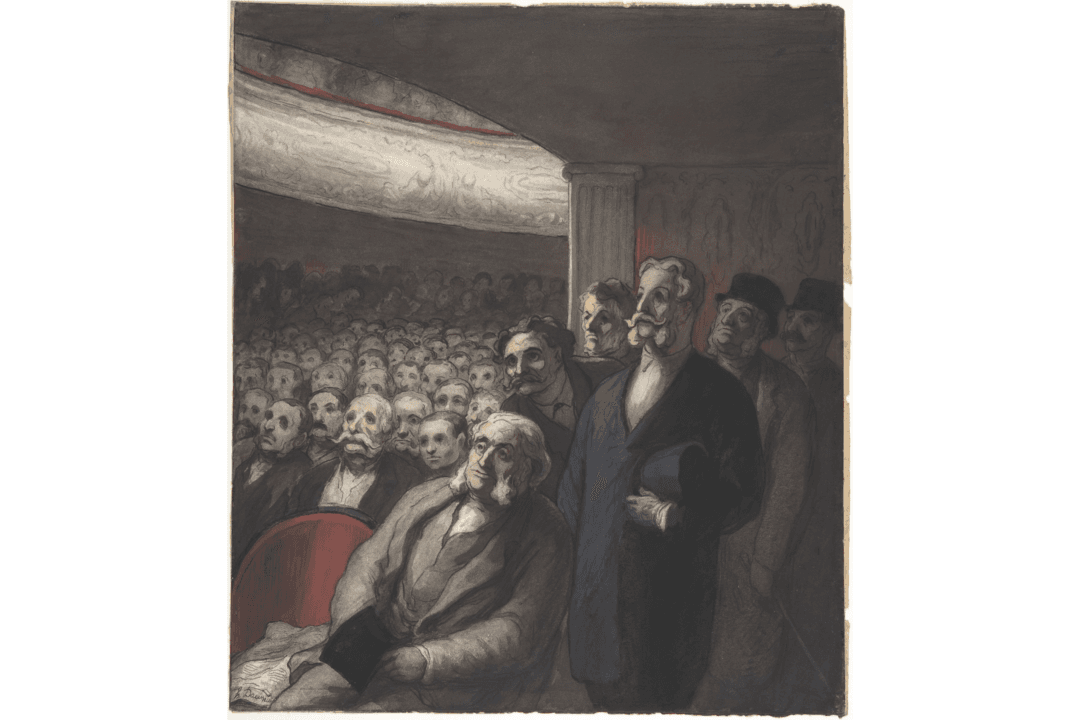

Yet this, in fact, is often called the “real” perspective by internment camp scholars. My own research into internment camp life suggests something different: The young Nisei (American citizens of native Japanese parents) were understandably bewildered by their imprisonment and demonstrated their patriotism through, among other means, theater.