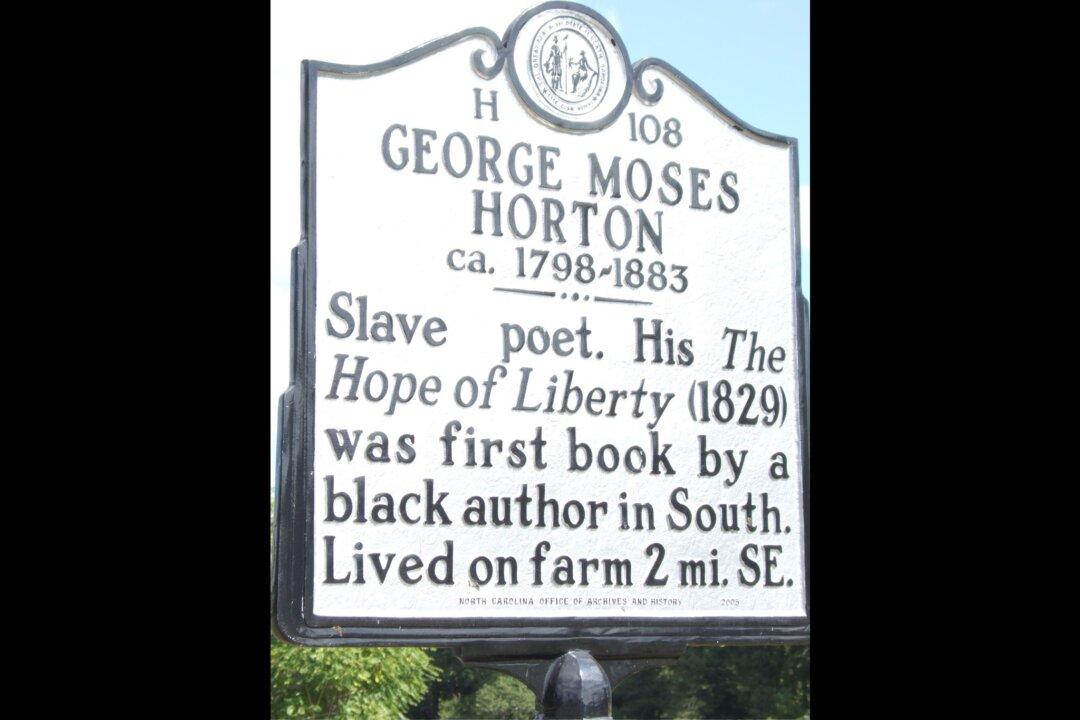

Approximately 67 years before the end of the American Civil War, George Moses Horton was born. He grew up a slave to the Horton family in North Carolina. While working on the tobacco plantation, his mind freely traversed the world of verse and rhyme. Using old hymnals, he taught himself to read, while also learning the poetic structure of stanzas.

Horton did not officially learn to write until his 30s, but his adaptation to the written word was so pronounced that he could construct his own poems and memorize them without writing them down. Eventually, those poems would be written down by others. But before they ever reached pen and paper, he found not only an audience of listeners but also buyers. When his master, James Horton, would send him to Chapel Hill for work-related business, he would venture to the University of North Carolina. Students, enthralled with his verses, would purchase lines from him for their own romantic purposes.