Ask any writer. Often the most poignant of insights come right after an interview ends, when the notebook is closed, the recording device is off, and often when the conversation goes completely off topic. That’s exactly what happened to me last year. I’d just had a fascinating interview in London with a well-respected art collector from a renowned family of art collectors. As I was packing up, my interviewee asked me where I was going next.

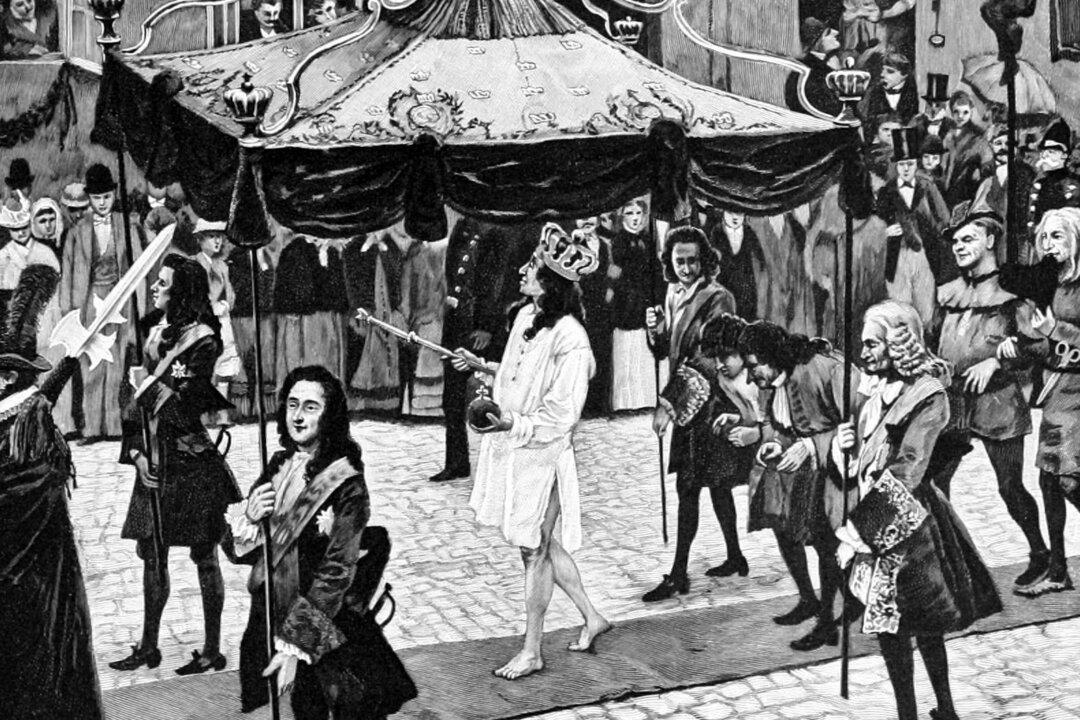

I’d booked to see the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, a magnificent Baroque banquet hall painted by British artist Sir James Thornhill, which took him 19 years to complete. The hall was designed by architect Sir Christopher Wren. If you haven’t heard of the hall you may have seen it onscreen, as it’s often featured in movies and in TV costume dramas. I hadn’t seen the hall since it had undergone extensive conservation efforts. As I was telling her that that’s where I was heading, the thought of seeing the hall filled me with so much joy that my eyes brimmed with tears.