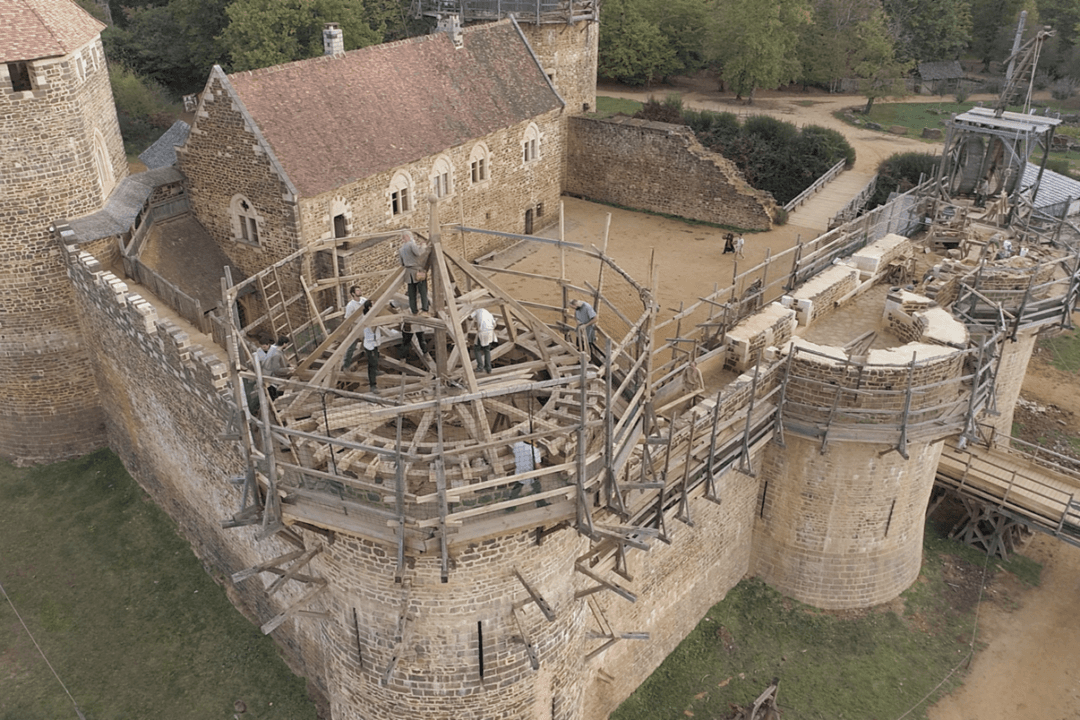

GUÉDELON, France—What was once one man’s pipe dream has turned into a reality by “The Lady of the Castle” Maryline Martin, the driving force that is making Guédelon happen. Guédelon castle was the brainchild of Michel Guyot, who wanted to a 13th-century castle to be built in 21st-century France—using Medieval methods.

Min entrance Guédelon 2023. Courtesy of Guédelon