On a cross-country road trip, I rambled into Estes Park, Colorado. There, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, magnificent scenery abounded. What I remembered most were the elk! With almost 300,000 elk living in Colorado, Estes Park becomes the breeding ground for these majestic creatures during the elk rut.

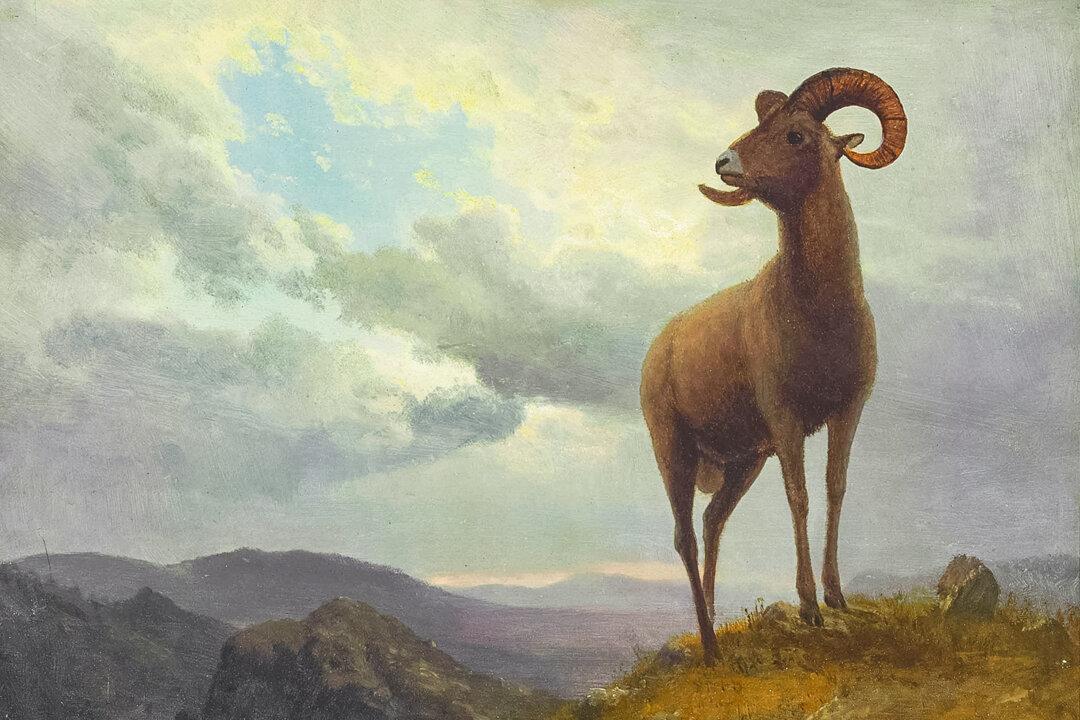

The great American landscape painter Albert Bierstadt once visited Estes Park during one of his Western expeditions. In his 1877 composition of “Estes Park, Colorado, Whyte’s Lake,” he painted the Rocky Mountains with the famous elk in the foreground. Although that man-made lake no longer exists, one can look across Jenny Lake to the Tetons and be greeted by a similar view in Wyoming.