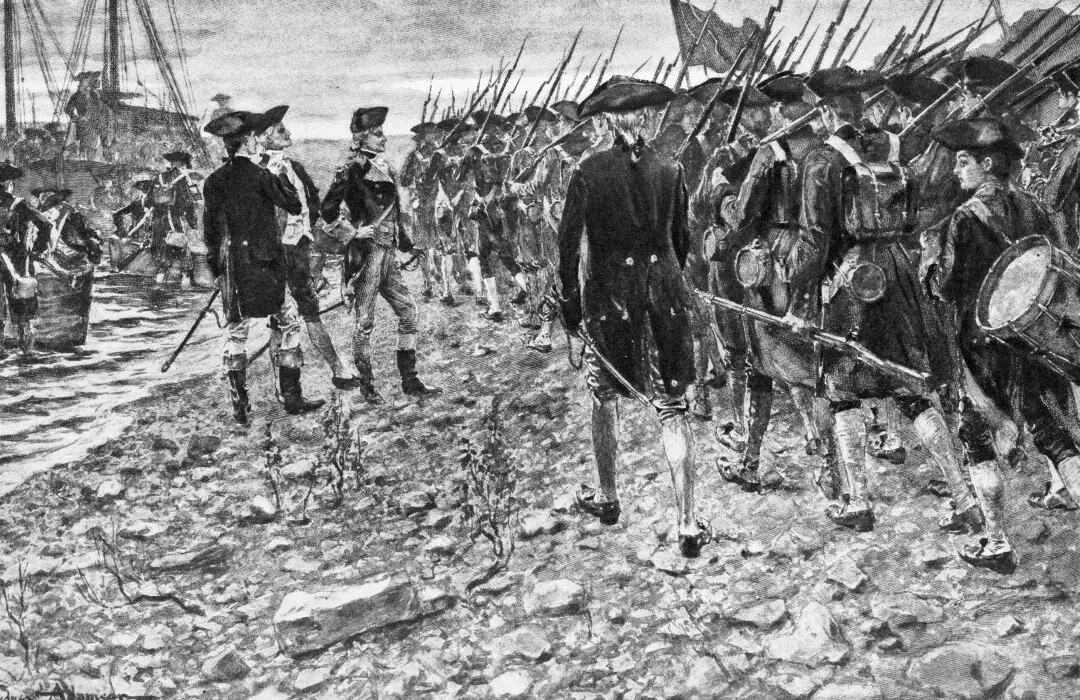

British Redcoats occupied Boston on Oct. 1, 1768, to end the civil unrest that divided the city between patriots led by The Sons of Liberty, and Tory loyalists led by Gov. Francis Bernard, Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and his brother-in-law Andrew Oliver. Siding with the patriots were the North and South Side gangs, led Samuel Swift and Ebenezer Mackintosh, respectively. Mackintosh later participated in the Boston Tea Party.

At issue were taxes, duties, and mercantile policies imposed upon the American colonists by Britain’s Parliament after the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War in North America). Because they lacked representation in Parliament, most colonists refused to abide by these new laws and responded with civil disobedience. Merchants purchased smuggled goods, and The Sons of Liberty organized boycotts of all British imports. This created problems on both sides. John Hancock had his sloop, the “Liberty,” seized for smuggling in May 1768, and customs officials were beaten in response. Those who enforced the laws, including Hutchinson and Oliver, had their homes and offices ransacked, and their effigies burned. The chaos that ensued forced Gov. Bernard to contact London and request soldiers to help restore order.