’Twas the early evening of Christmas Day in 1776 and Gen. George Washington was on the verge of losing the Revolutionary War. His armies felt defeated and discouraged, his countrymen had lost confidence in his abilities, his adjutant-general Joseph Reed had conspired against him, his second in command Charles Lee had been captured two weeks prior on Friday the 13th, and Gen. Horatio Gates was off currying favor at his expense with the Continental Congress, which had fled Philadelphia for Baltimore days earlier.

A Desperate Gamble

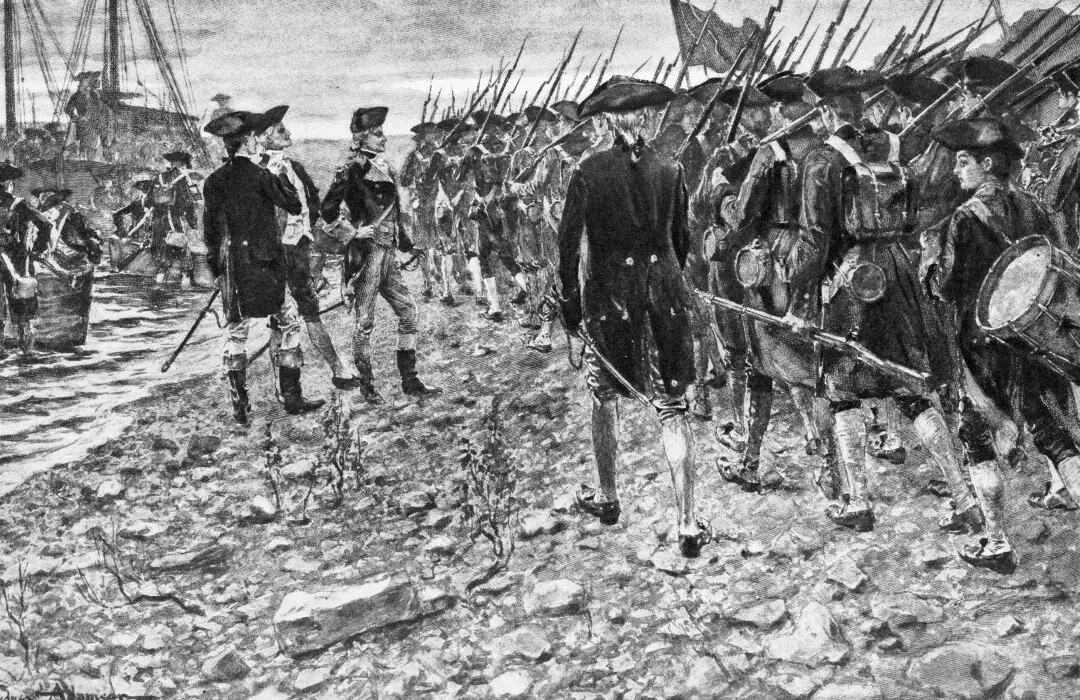

With his men’s enlistments expiring in one week, Washington had no choice but to risk everything on a desperate gamble he hoped would save the cause. His plan was to split up the approximately 5,000 men left under his command into three coordinated strike teams, cross the Delaware River, surround the Hessian-occupied town of Trenton, and attack an hour before sunrise.As he looked across the river from McConkey’s Ferry toward New Jersey, Washington must have reflected on the disastrous events that had led him to this point. When independence was declared in July, he commanded approximately 20,000 men, albeit undisciplined and poorly trained. His opponent Gen. William Howe commanded 32,000 highly-trained and better-equipped British soldiers and German mercenaries.