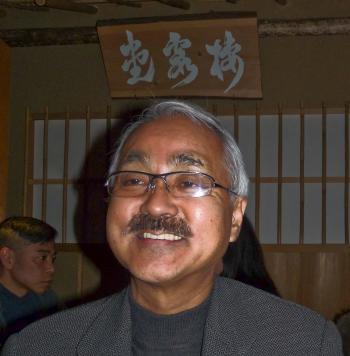

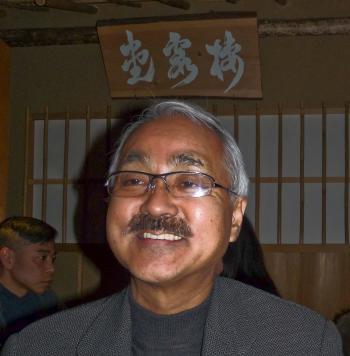

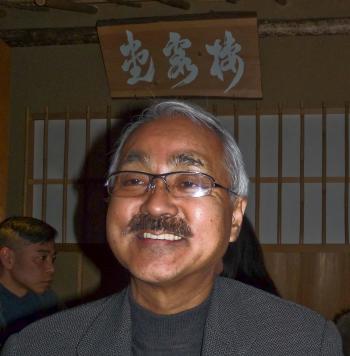

I met Mr. Yagi in his New york office. He conducts his business above a traditional Japanese teahouse, Cha-An, just one of his many creations. Mr. Yagi is founder and president of the T.I.C. Group. Looking through the window, he chose to be addressed Yagi in an almost shy, wistful tone, rather than the formal Shuho Bon Yagi.

His comment, “I am the last immigrant from Japan,” aroused my curiosity. He referred to the year 1968, a year of upheaval and skirmishes in his homeland, when the United States pressured Japan to halt Japanese immigration into the United States.

As sometimes happens in life, unexpected twists and turns change one’s fate. Yagi missed his Japanese college entrance exam by ten minutes. Since he was not interested in the events of Japan’s political upheaval then, he took his college tuition money and, like many before him, decided to come to the United States. He sailed from Yokohama to Honolulu, then on to San Francisco, a 12-day voyage. On arriving in San Francisco, he immediately boarded a bus to the ghettos of Philadelphia, where the African-American soldier he met in Japan lived. He hoped this person would be his connection to Yagi’s yet undetermined American future.

America, the dream destination for so many immigrants, proved an initial disappointment. Instead of encountering streets paved with gold, he found huge differences between the haves and the have-nots and racial discrimination.

Because of his promise never to return to Japan unless he was successful, he held menial jobs at a small diner in Philadelphia and eventually advanced to the position of short-order cook.

His experience making omelets and burgers made him realize the untapped potential of introducing Japanese food to American palates. A better-paying job as bartender allowed him to save money. He traveled the globe to get a feel for what people around the world eat, and what they might want to savor in the future.

Having trekked through Europe, the Mediterranean, Turkey, India, and Pakistan, he returned to Japan, making and selling jewelry in the streets of Tokyo. That venture brought him sufficient capital to return to the United States and open his first restaurant, Mr. Yakitori, at Martha’s Vineyard, a seasonal operation.

The venue introduced American diners to the Japanese specialty Yakitori, chicken on skewers. He brought a special piece of equipment for this process from Japan. One New York restaurant is still using this machine today. No one else served this style of Japanese food then. The Tapanyaki-Benihana style of food preparation was popular, using a flat metal tableside griddle. Once again he lacked money to open a Yakitori restaurant in New York, but his best friend Wakayama, who now owns East and Teriyaki Boy, helped him.

These two innovative friends doubled the number of scarce Japanese vegetable vendors in the city, from two to four. They had no start-up costs and charged $1 per bag of produce delivered. Their business grew rapidly.

His comment, “I am the last immigrant from Japan,” aroused my curiosity. He referred to the year 1968, a year of upheaval and skirmishes in his homeland, when the United States pressured Japan to halt Japanese immigration into the United States.

As sometimes happens in life, unexpected twists and turns change one’s fate. Yagi missed his Japanese college entrance exam by ten minutes. Since he was not interested in the events of Japan’s political upheaval then, he took his college tuition money and, like many before him, decided to come to the United States. He sailed from Yokohama to Honolulu, then on to San Francisco, a 12-day voyage. On arriving in San Francisco, he immediately boarded a bus to the ghettos of Philadelphia, where the African-American soldier he met in Japan lived. He hoped this person would be his connection to Yagi’s yet undetermined American future.

America, the dream destination for so many immigrants, proved an initial disappointment. Instead of encountering streets paved with gold, he found huge differences between the haves and the have-nots and racial discrimination.

Because of his promise never to return to Japan unless he was successful, he held menial jobs at a small diner in Philadelphia and eventually advanced to the position of short-order cook.

His experience making omelets and burgers made him realize the untapped potential of introducing Japanese food to American palates. A better-paying job as bartender allowed him to save money. He traveled the globe to get a feel for what people around the world eat, and what they might want to savor in the future.

Having trekked through Europe, the Mediterranean, Turkey, India, and Pakistan, he returned to Japan, making and selling jewelry in the streets of Tokyo. That venture brought him sufficient capital to return to the United States and open his first restaurant, Mr. Yakitori, at Martha’s Vineyard, a seasonal operation.

The venue introduced American diners to the Japanese specialty Yakitori, chicken on skewers. He brought a special piece of equipment for this process from Japan. One New York restaurant is still using this machine today. No one else served this style of Japanese food then. The Tapanyaki-Benihana style of food preparation was popular, using a flat metal tableside griddle. Once again he lacked money to open a Yakitori restaurant in New York, but his best friend Wakayama, who now owns East and Teriyaki Boy, helped him.

These two innovative friends doubled the number of scarce Japanese vegetable vendors in the city, from two to four. They had no start-up costs and charged $1 per bag of produce delivered. Their business grew rapidly.