We looked in Part 1 at the mythological origins of Truth (Veritas) and Lies (Mendacium). We established that they were like twins: sometimes very difficult to distinguish between one and the other. And we made the point, too, that Mendacium, because she was footless, was immobile and also unbalanced. If we think through what this imagery means—keeping in mind that the myths tell us deep psychological or even spiritual truths—we realize that being footless, being immobile, means that we are not free. The essence of being free is that we are free to move, wherever and whenever we want. If at any point in our lives we cannot move, we cannot truly be said to be free.

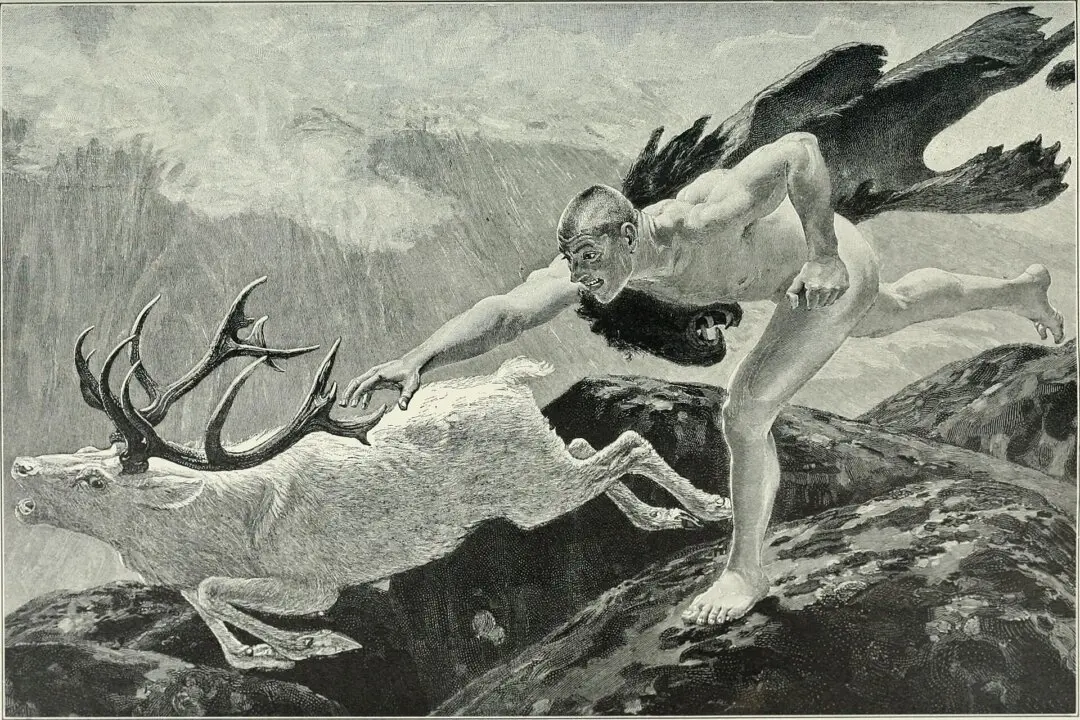

While truth and lies can look the same, they are like identical twins, who can be very different indeed, as the painting “The Twins, Kate and Grace Hoare” (1876), by John Everett Millais, suggests. Kate (L) holds a riding crop and her demure sister, a hat. The Fitzwilliam Museum. PD-US