In the kitchen of a small, two-bedroom Brooklyn apartment, a young Ebow Dadzie watched his grandmother cook. At times, he was instructed to pass a spice or stir a pot, and sometimes he was taught an entire recipe. Usually, he just observed as Dorothy Mitchell prepared dinner for her family. No matter what he was doing, Dadzie was always learning. Mitchell was a Trinidadian immigrant, as no-nonsense as grandmothers come, and an ox-like woman (Dadzie’s words) who would work magic with curry in one breath and whoop a naughty grandchild in the next. “You talk about a woman that knows how to grind, that knows hard work, she was all that,” Dadzie said of his grandma. “She made sure everybody’s belly was full at the end of the night. There’s a term you use when you’re poor, it’s when you don’t get to eat, you ‘eat sleep for dinner.’ She made sure we didn’t do that.”

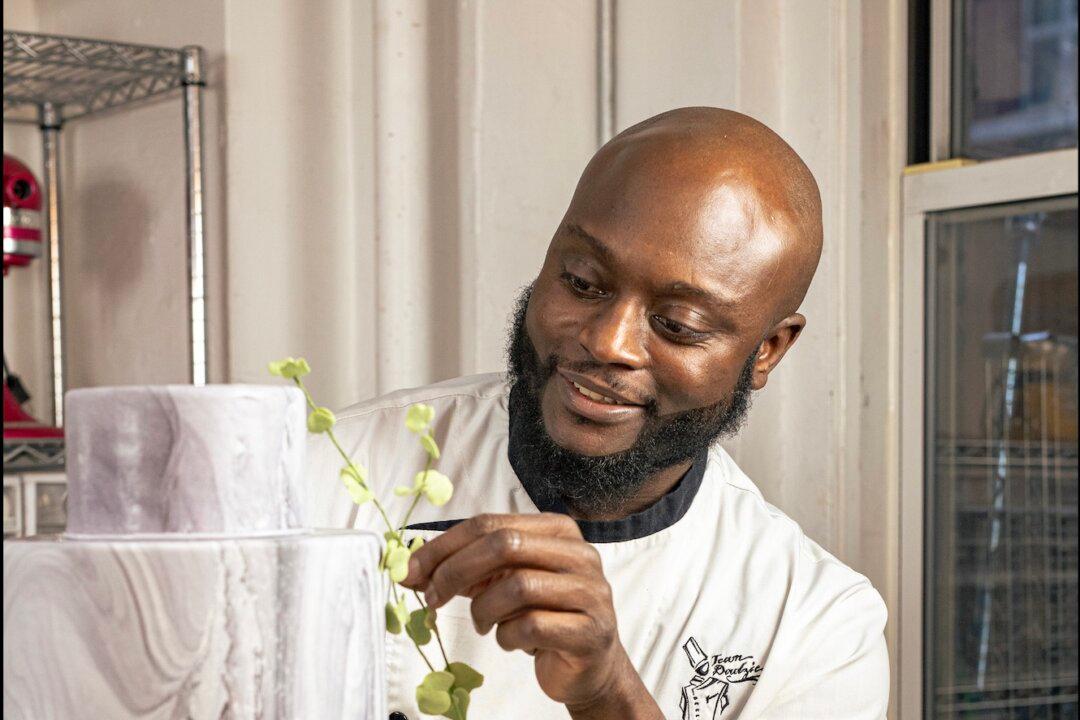

Dadzie has come a long way since the tiny kitchen perfumed with the simmers and stews of Trinidadian cooking and the warm place of childhood memory where a black-and-white TV used to play the show Video Music Box over opened textbooks on a nicked and well-loved table. Dadzie, who was named among the Top Ten Pastry Chefs in America by Dessert Professional magazine in 2014, has built both literal and metaphorical skyscrapers. In 2006, he built a 16-foot replica of the Empire State building for a Food Network competition, which won the Guinness World Record at the time. He also paved the way for black pastry chefs to enter the fine baking competitive community. And that’s just so far; he’s got plenty a ways to go—but not before remembering where he came from.