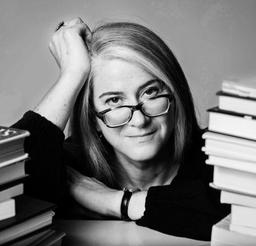

NEW YORK—As his photo was being taken, Burton Silverman instinctively held on to a bunch of his paintbrushes with a relaxed, yet determined grip—the way a relay racer holds onto a baton. Painting with a fondness for everyday life, Silverman has been holding and passing on the baton of realist art for more than six decades. He has done so without purposeful intent. He simply continues to communicate the spark of what he sees and of what may otherwise go unnoticed.

In the midst of his endless process of refining an already developed artistic voice, he talked about his creative process, in his studio on the top floor of his brownstone home on the Upper West Side.

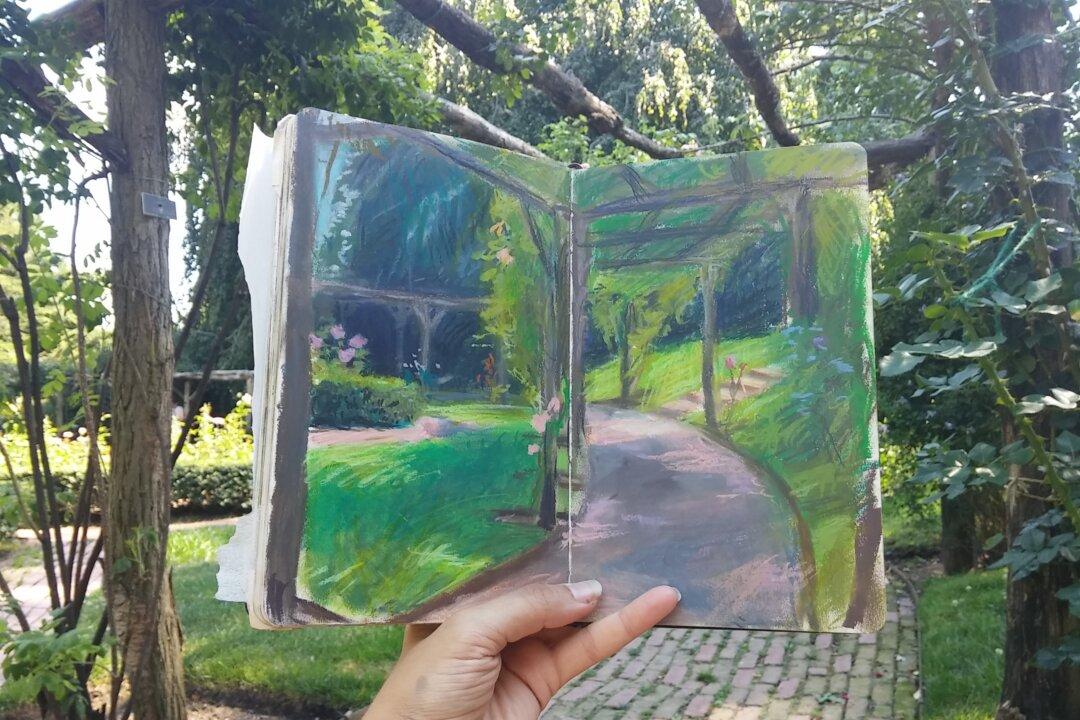

“It doesn’t start with any grand idea for me. When I am making a painting, it comes from the most incidental of events,” Silverman said.