In the mid-18th century, European artists, art admirers, and collectors were keen to view the finest artworks from across the continent, in the comfort of their studios, homes, and studies, respectively. Prints fulfilled that need, and as the demand for fine art prints grew, printmaking innovations blossomed.

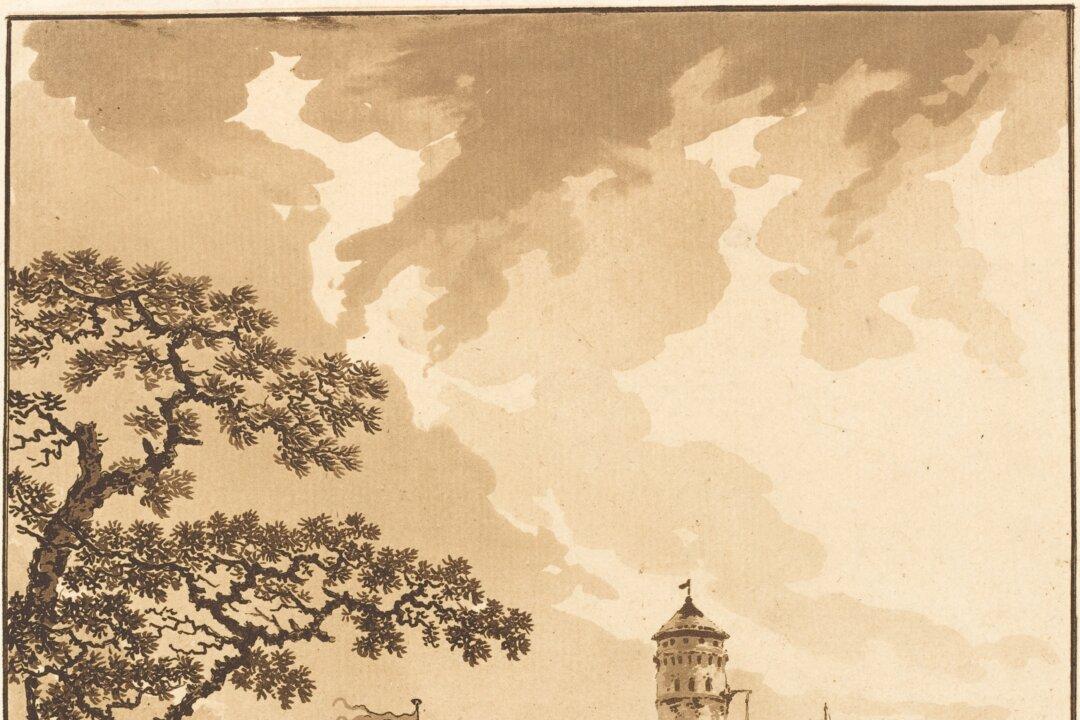

One such innovation was a painterly printmaking technique that you’ve probably seen but maybe not heard of: aquatint. Aquatint is an intaglio printing technique (involving incisions applied to a metal plate) used in conjunction with etching, which allows artists to effectively mimic the subtle tones of ink, wash, and watercolor.