John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s fantastical world of Middle-earth may be make-believe, but for Tolkien it had a real purpose: It was a land where he could create a rich tapestry of myths and legends for England—specifically, for an England that he felt had been robbed of its cultural heritage by the Norman Conquest.

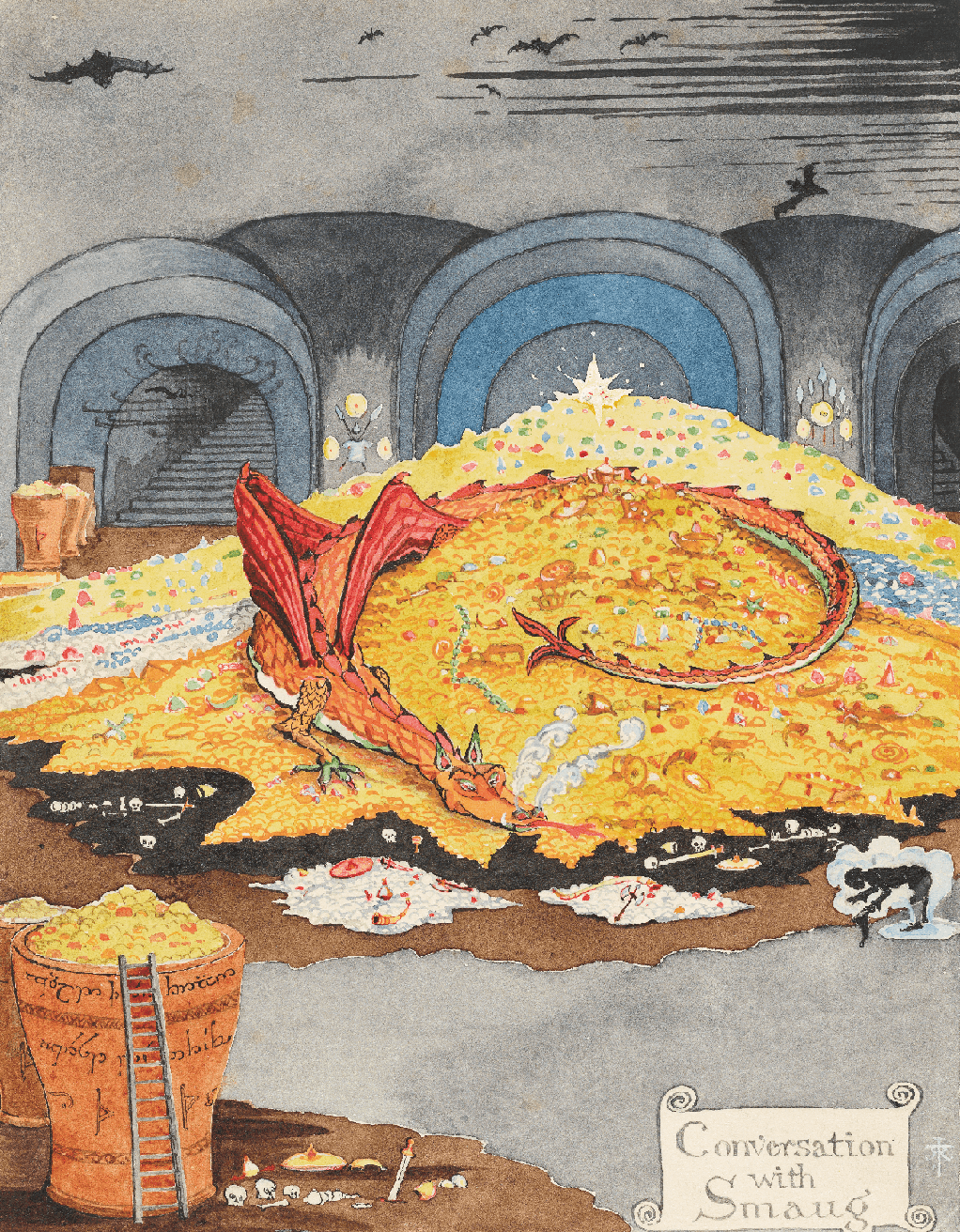

“Conversation with Smaug,” July 1937 by J. R. R. Tolkien. Black and colored ink, watercolor, white body color, pencil. Bodleian Libraries. The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937