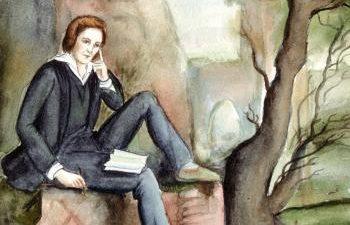

An Essay on Man Know then thyself, presume not God to scan, The proper study of mankind is man. Placed on this isthmus of a middle state, A being darkly wise, and rudely great: With too much knowledge for the sceptic side, With too much weakness for the Stoic’s pride, He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest; In doubt to deem himself a God, or beast; In doubt his mind or body to prefer; Born but to die, and reas’ning but to err; Alike in ignorance, his reason such, Whether he thinks too little or too much: Chaos of thought and passion, all confused; Still by himself abused or disabused; Created half to rise, and half to fall; Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all; Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled: The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!

—Alexander Pope (1688–1744)