Book Review: Hell on Earth

A vacation in Alaska kicked off a terrible walk down memory lane for author Ludwik Kowalski when he spotted a plaque in an Anchorage souvenir store.

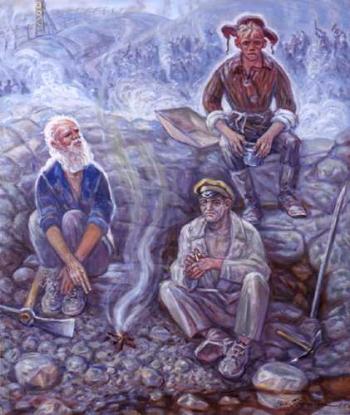

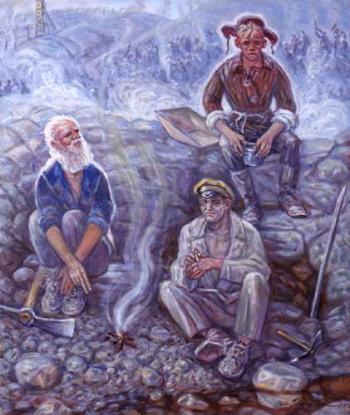

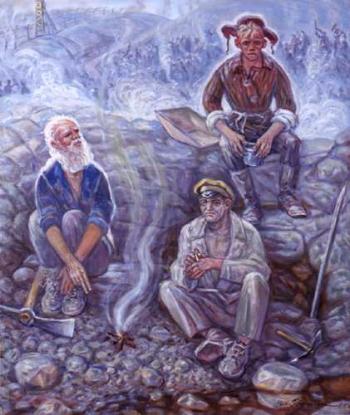

SPIRITUAL SUPPORT: In his painting, The Preacher, Nikolai Getman shows an Orthodox Christian encouraging two prisoners who, with him, were sent to a Siberian death camp to work and die. courtesy of jamestown.org

|Updated: