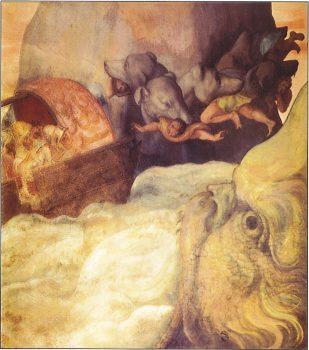

Odysseus’s ship passing between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis, by Allessandro Allori, circa 1575, from a fresco. Public Domain

Homer’s “Odyssey” is, by common and universal consent, one of the greatest poems in the world, possibly the greatest. Certainly, as far as Western culture is concerned, the very word “odyssey” has become synonymous with an epic journey, and more precisely the journey home: not merely literally, but also symbolically, as Odysseus finally achieves reunion with Penelope, or his own soul, or anima.