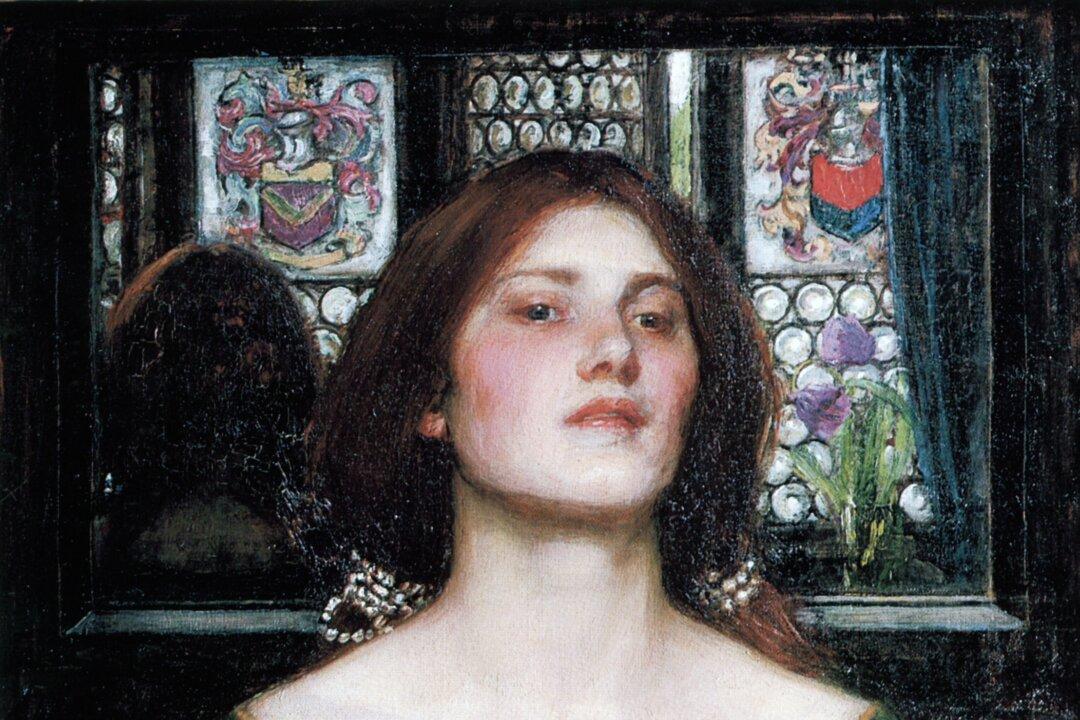

To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying: And this same flower that smiles today Tomorrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun, The higher he’s a-getting, The sooner will his race be run, And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first, When youth and blood are warmer; But being spent, the worse, and worst Times still succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time, And while ye may, go marry: For having lost but once your prime, You may forever tarry.

Tempus Fugit. Time flies. The flower blooms and withers. The sun rises and sets. Youth decays to the grim certainty of death. The basic truths of life never change, no matter our fractious desire for novelty.One of poetry’s great powers is to remind us of the obvious, while we distract ourselves with the merely sophisticated. In this deceptively simple yet teasing work, Herrick reminds a bevy of virginal maidens (no doubt imaginary) not to fritter away their irreplaceable youth but to make something of it.