What does the story of the great ancient warrior Capaneus have to do with technology today? Or with the myth of Frankenstein, for that matter?

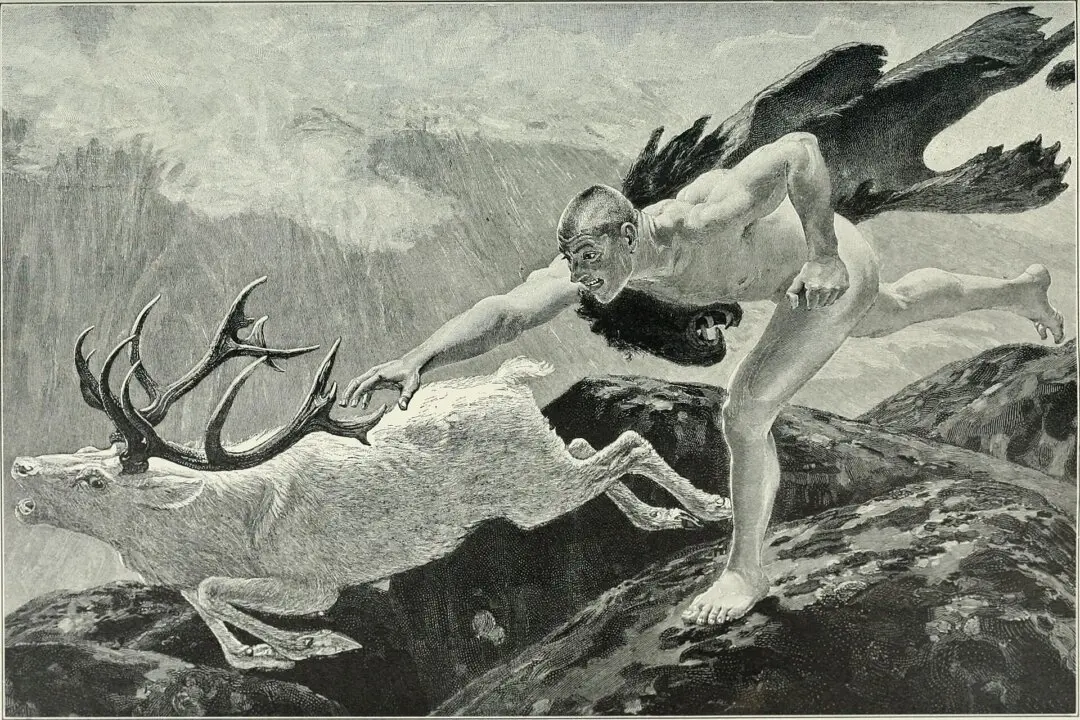

In our first article in this two-part series, we looked at how the myth of Frankenstein (and its Greek-related story of Prometheus) was a warning to us about the dangers of the technological age we live in. Two aspects of the danger were, on the one hand, the scale of the monstrosities that humans might “create” (for example, atomic weaponry), and on the other, the fact that technology might get out of hand and become not only uncontrollable but also the master who dictates to and controls human beings (such as Artificial Intelligence). But I indicated at the end of the article that another Greek myth, much less well-known, speaks potently to our condition today.