We have plenty of modern myths to help explain what is going on in the world today. Perhaps the greatest of all is the one written at the dawn of the modern world, just preceding the Industrial Revolution beginning in Britain in the 19th century. That rapid scientific development established Britain as the world’s No. 1 power for nearly a century until the end of World War II. The myth is Frankenstein.

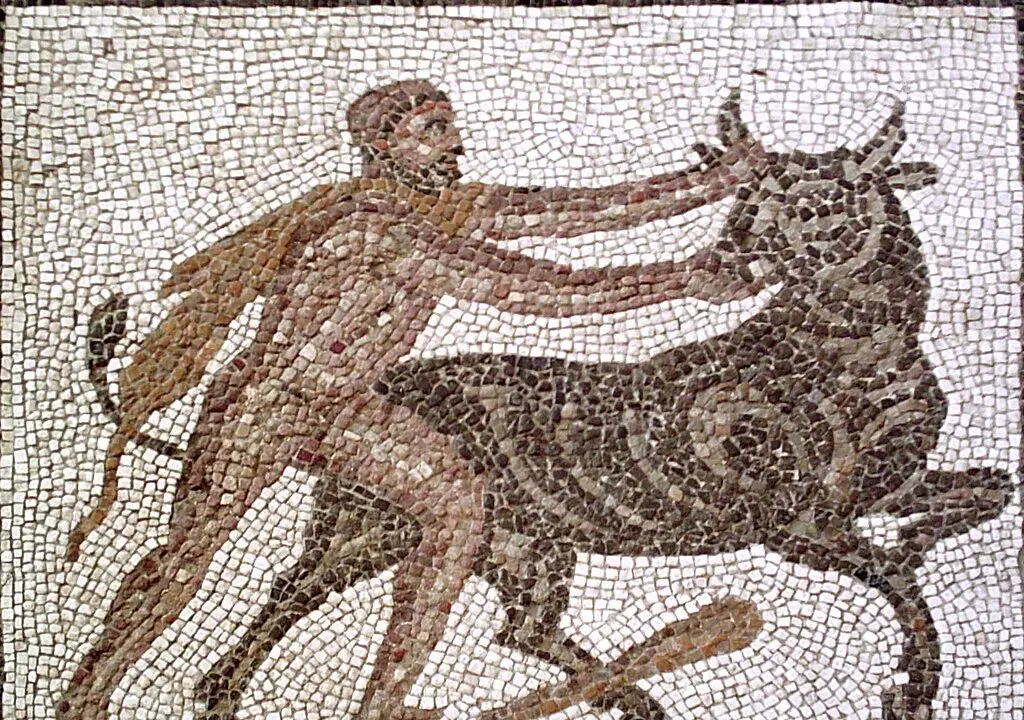

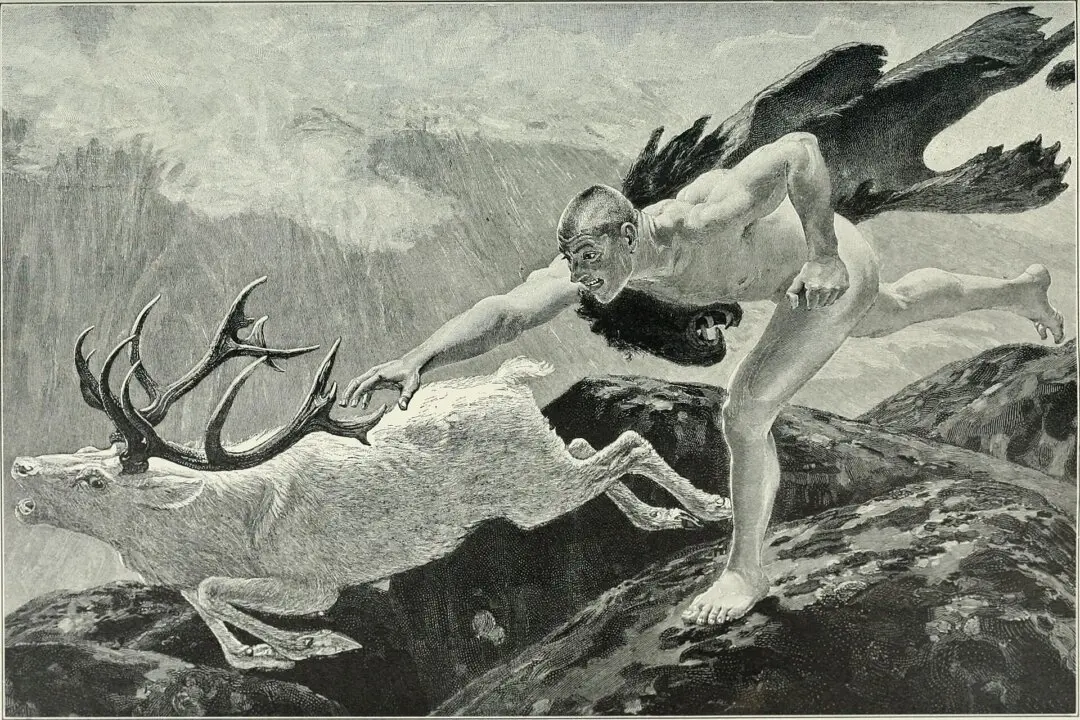

Myths epitomize the depths of ancient thinking but in symbolic, imaginative, and narrative forms that speak for all time. Invariably, they bridge the gap between what is visible—our world now—and what is invisible: the emotional, psychological, and even spiritual reality where a different order of being has precedence.