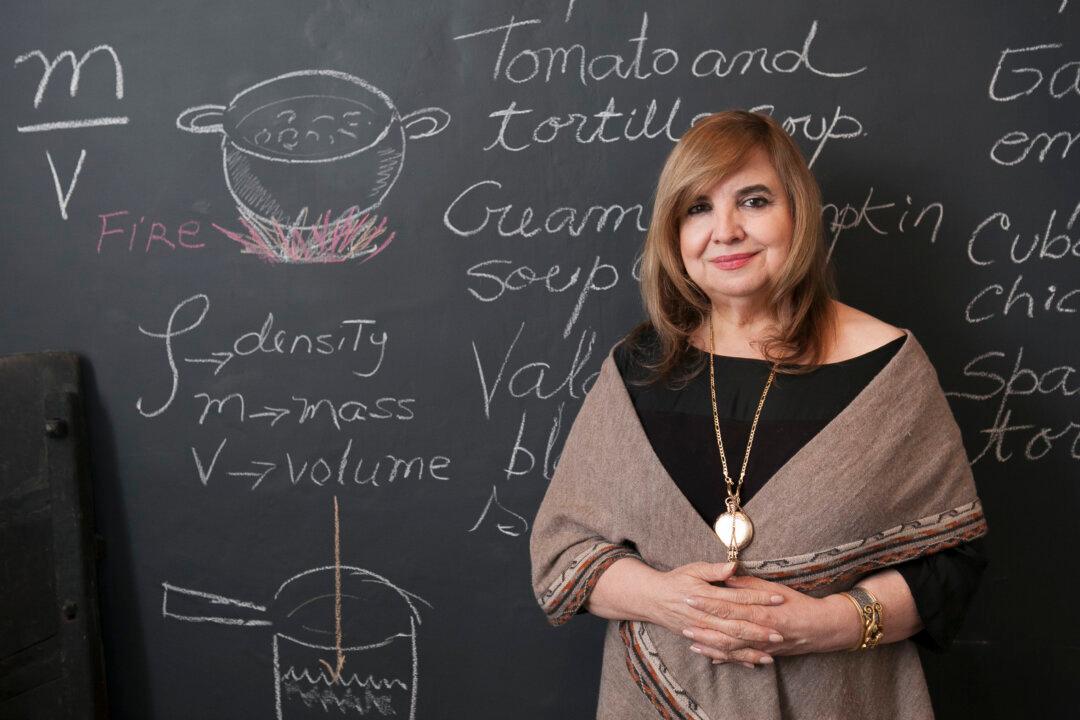

“I am a cucharamama,” Maricel Presilla said. “A mother spoon.”

In Ecuador, she explains, it is the largest spoon in the house, the one that women use to make soup for their families, to smack naughty children, and shoo away the misbehaving guinea pigs called cuy.

It’s a utilitarian tool, but also a symbol of power.

The mother spoon also symbolizes the power of enterprising women: women who everywhere hold power through cooking, or through the selling of their food at the marketplace.

Presilla is a James Beard Award-winning chef, chocolate judge, explorer, medieval historian, collector of textiles, keeper of birds—a Renaissance woman with vast-ranging interests and vast-ranging and endless curiosity.

She recalls a street food spot that she loves near Oaxaca, Mexico, “You sit there and you imagine you’re in this woman’s kitchen because that’s how the transaction is done.”

It’s the same with her Hoboken-based restaurants, Zafra and Cucharamama. And her artisanal food store, Ultramarinos, which means “from beyond the sea,” and is named after the provisions store Spaniards would set up with goods they had found in the New World.

“I’m just trying to recreate my home outside. This is the essence of my home kitchen I’m serving you,” she said.

‘Gran Cocina Latina’

Over the last three decades, much of her energy has been directed to her James-Beard award-winning 2012 book, “Gran Cocina Latina,” which documents recipes from all over Latin America. “This book is the history of my life,” she said, so much so that all of her businesses, run with business partner Clara Chaumont, are based on recipes from the cookbook.

It’s a cookbook that took about 30 years to put together, not only a compendium of recipes, but also personal stories and, given her training as a medieval historian, a unique perspective on the history of food in Latin America.

It was meant to start as a Cuban cookbook. But not only wasn’t it possible—she was restricted from traveling freely through her native Cuba—it also didn’t seem right to get recipes from people for whom food was hard to come by.

She returned a few years ago on assignment for Saveur magazine and was shocked by the poverty and destruction that had befallen her home island. “But when you’re a journalist, you’re like a bird perched above all this sadness, you are examining things because you have an assignment to do, so you cannot fall into depression. … That saved me because I saw so much destruction.”

When she went back to her hometown of Santiago de Cuba, she found her grandmother’s kitchen unusable. It was broken. To get ingredients for her story, she had to depend on the black market and buy with dollars. “It was such a lie … nobody was eating that way.”

“People really do marvelous wonders to get food,” she said. “It seems bountiful but it isn’t, because people really go through hell to get something to eat.”

In the end, she opted instead to head to eastern Cuba, where her grandmother’s relatives farmed and lived. “I said, if they really cook and have this great food, I'll cover it.”

The journey was anxiety-ridden. Presilla had hired a car and driver from a private individual, both of which are forbidden. “If they had found me with an American passport, in a private vehicle, they would have taken the car from him, and put the guy in jail,” she said.

Finally, they arrived at the mouth of a river, the point at which, she remembered from her childhood, you could only drive to, and then there would be horses to take you the rest of the way through the mountainous area.

“I imagined that this time, after so many years, there would be a road.” There was no road and no horses.

She was told they would have to drive up through the riverbed. They did, but got stuck and the water started rising. “It was a disaster. I said, ‘This is the end.’”

As it happens so often in her stories, in the middle of a bleak situation, a ray of hope came shining through, this time in the form of an army truck coming full speed through the river bed. The driver stopped.

“He was totally drunk. He was a skinny, wiry guy with bronze skin. He had a bottle of moonshine in one hand, and no shirt,” Presilla said. He was also going to her family’s farm to get coffee.

He harnessed a rope from Presilla’s Jeep to his own truck. Presilla’s aunts, in their 80s, stayed in the Jeep, while he pulled them out. “He said to me, we’re going to get stuck many times. So every time we get stuck, I need to go down and check to see what’s happening, and you have to put your foot on the clutch. And every time that happened he would hand me the moonshine bottle. I was terrified I would do something wrong and the car would go down the hill.”

They finally arrived at the farm in the late afternoon. “So many people who looked like me came out—the genes!” she said.

Her efforts were worth it. She chronicled her journey in an article titled “My Eternal Cuba,” which was nominated for a James Beard award.

Connections

Some lucky star has been watching over Presilla.

More often than not, during her years traveling through Latin America, she found commonalities, and extraordinary coincidences.

Once, in Cartagena, Colombia, she was looking for a taxi. Being particular about taxi drivers, she skipped the first one, and picked the second one.

It turned out the driver was related to the people she was going to see. He started singing an old Mexican song that she knew. “I kept thinking, all this distance, and yet we’re so connected through music, through songs, through a kind of Spanishness that joins us together. It was just amazing.”

Points of Intersection

Presilla’s perspective as a medievalist renders the history of food in Latin America alive. Through her lens, it’s possible to understand the connections, big and small, that bind the different strands of culinary history.

In “Gran Cocina Latina,” she mentions the history of a dessert called tajadón. “It’s an egg cake. You beat egg yolks—like an unmentionable number of egg yolks—and you cook them. You make a cake, you add hot syrup, It’s really delicious. It’s yellow and beautiful.”

She thought it was decidedly Cuban until she was told otherwise, “No, it’s Peruvian; no it’s Mexican.”

There are desserts, Presilla said, that every nation claims as their own, but actually came from Spain by way of the nuns.

“There are things that are so pan-Latin … because of the Spaniards that took either that recipe or took that concept and spread it everywhere.

“And when you know how the nuns were—they were in the monastery in the Dominican Republic, but they could be sent to Peru. The church breaks down national barriers. So when you’re a nun, you’re not a Dominican nun, you’re a nun. So you might spend your time in the Dominican Republic, go to Habana, and then get sent to Lima. So they were the carriers of pastry, sweet traditions.”

There are points of intersection. Wherever you find blacks, there are particular types of food, Presilla said. One example is the bolon de verde, a plantain mash with pork cracklings, found in the Esmeraldas, a coastal area in northern Ecuador, where there is a large black population.

“We call it fufu. You go to the Dominican Republic, it’s mofongo. All of us have a version of that.”

When Spaniards came to South America in the 16th century, they brought plantains with them.

“When you go to the Amazon, with the Yanomami, their favorite soup is made of plantains,” Presilla said. “Who tells these people plantains are not theirs? It’s a staple.”

In the course of researching for “Gran Cocina Latina,” Presilla used her own funds, rather than relying on government grants, for example, and was able to go wherever she wanted. What she found, besides stories and recipes and culinary connections forged through history, were connections of her own: lifelong friends, godchildren, as if the whole of Latin America was just one small street corner.

“You find yourself no matter where you go. You find parts of you,” she said.

Leaving Cuba

Presilla left Cuba in 1970, with her parents and younger brother. It wasn’t a decision they made lightly, but they saw no other way.

“The repression was fierce. It was a hard decision because it meant leaving everything,” she said. “It was like Hernan Cortés—you had to burn the boats. As soon as you made the decision, you became a target. If you were working, the Cuban government punished you. They sent you to the fields to do work. It was forced labor.”

Her parents were both professors; but they both lost their jobs. Presilla and her father were sent to the fields; her mother, because she had a younger child, did not have to go. Presilla was in prep school but forbidden from going to university.

“It was horrendously depressing. It was at the same time a situation that confirmed that we had to get out,” she said. They had no income, and her aunts would send them food. “My mother’s sisters were the ones who kept us going. They were going to leave the country but someone had to work. They were teachers. For us, they stayed behind. It was incredible. … It took my poor aunts years to be able to get out. They sacrificed for us.”

She and her family eventually arrived in Miami. She was later joined by her then-boyfriend, and now-husband, Alejandro Presilla, who had swum across to Guantanamo Bay. He was a slow swimmer, and swam all night, to be greeted in the morning by the sight of green fatigues, and his first Thanksgiving meal.