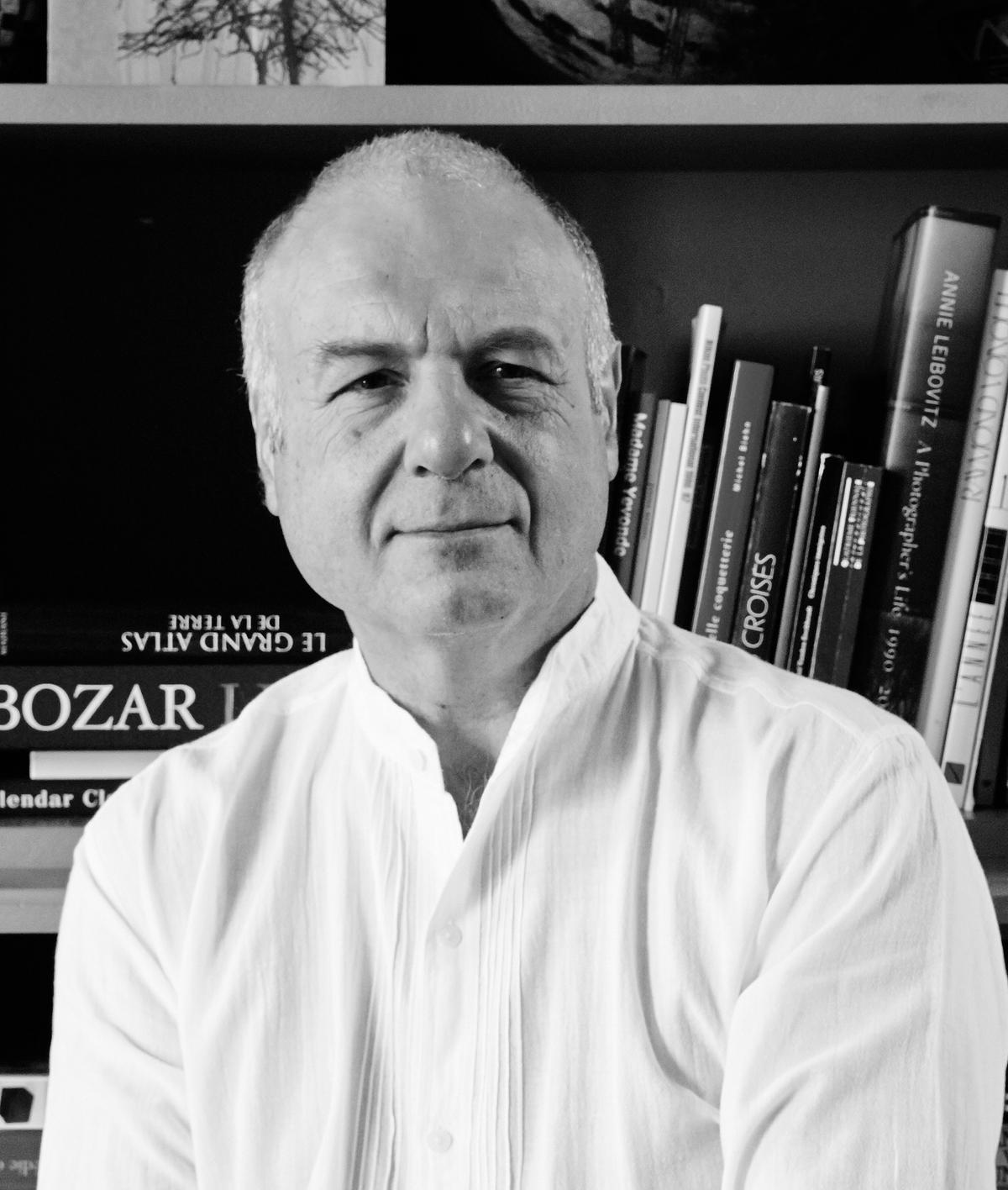

Combining an eye for the visual with an adventurous spirit, photographer and author Jean-Pierre Gabriel scoured the length of Thailand for three years. He unearthed a trove of cooks willing to share their culinary secrets and authentic recipes for dishes both iconic and unusual.

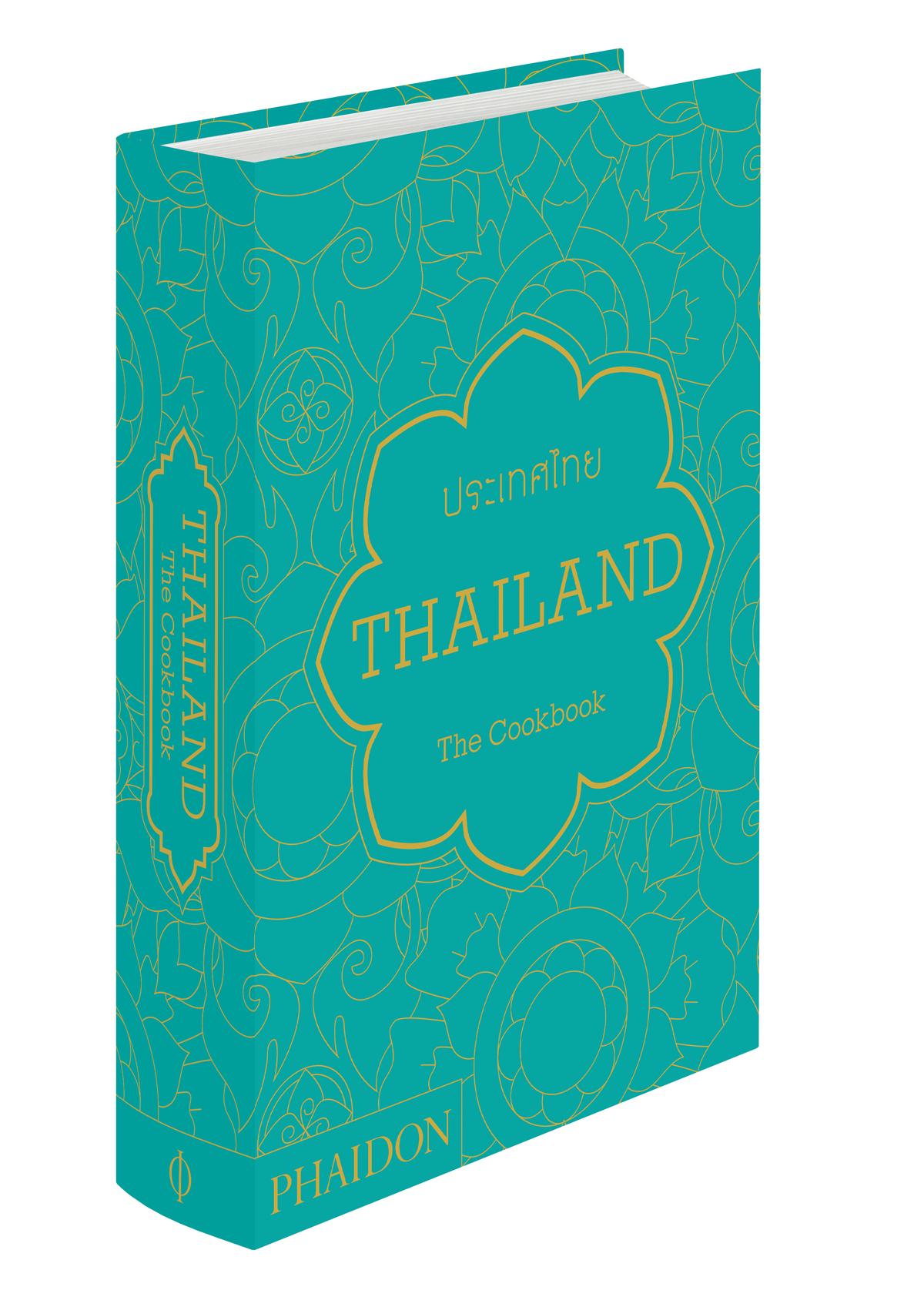

In the pages that follow, Gabriel shares his journey that created his new book “Thailand: The Cookbook” (Phaidon, 2014), and offers several mouthwatering recipes.

Q. What inspired you to undertake “Thailand: The Cookbook”?

A. I have never encountered a cuisine as fascinating as Thai. It seduces through its flavors—which come both from certain ingredients and legendary recipes—and the great sense of freshness it imprints on one’s memory.

From the start our project was fascinating. Our goal was to travel through most of the country, from the north to the south and to seek out diversity wherever it was. That’s what we did.

I like to understand history, development. I like to collect information to the last detail. There were mysteries in history that I tried to understand—without always succeeding. For example, how and when chilies arrived in Thailand and the trajectory they followed. Was it the Spanish or the Portuguese who brought them over?

It’s also astonishing that the central plains and Bangkok have, to this day, kept recipes based on egg yolks—typical of convent cooking in Portugal. The Portuguese were present in the court of Ayutthaya from the 17th century.

I like to meet people, which helps put things in context. Since I am also a photographer, I have a thirst for images, even those I don’t photograph and simply keep in my memory.

Q. What surprised you in the course of putting this book together?

A. There were many things. In part, the human aspect.

It seems like stating the obvious, but we need to eat to live. Different societies have different relationships to food. In Thailand today, you’ll find an immense variety of food-related behavior. Next to a 7-Eleven, where you’ll find industrial food, you’ll find a young woman who, in less than 1 square foot, prepares papaya salad in her mortar made of terra cotta.

In certain markets, I think in the northeast and the north, you find totally local things, whether insects, water buffalo skin, or tree barks with medicinal properties. And especially what you’ll find nowhere else—one of the roots used in Thai cuisine, black krachai, only grows in certain provinces in the north.