In the film “Mary Poppins,” Ed Wynn, Julie Andrews, and Dick Van Dyke sing “I Love to Laugh,” a hilarious song that sends Wynn and Van Dyke floating to the ceiling from sheer joy and exuberance.

Here is the final stanza:

The more you laugh The more you fill with glee And the more the glee The more we’re a merrier we.

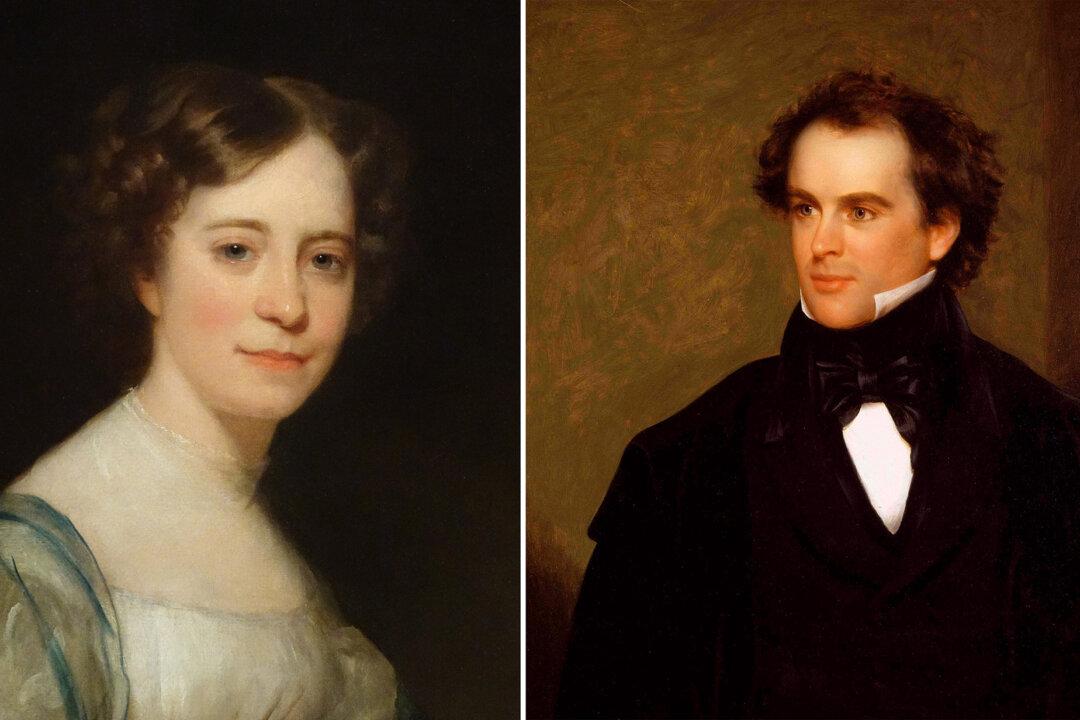

A piece on laughter, jokes, comedy, and humor may seem somehow out-of-place on an “Arts and Culture” page, but comedy is a core piece of our culture. Playwrights like Aristophanes and Shakespeare, a poet like Geoffrey Chaucer and his work “The Canterbury Tales,” and writers like Mark Twain, P.G. Wodehouse, and Lewis Grizzard all produced works that brought laughter to their audiences. The list of such writers is extensive, and their humor ranges from farce to satire, from broad, earthy humor that brings a belly laugh to sophisticated drawing room comedy—think Oscar Wilde—that produces a grin or a chuckle.