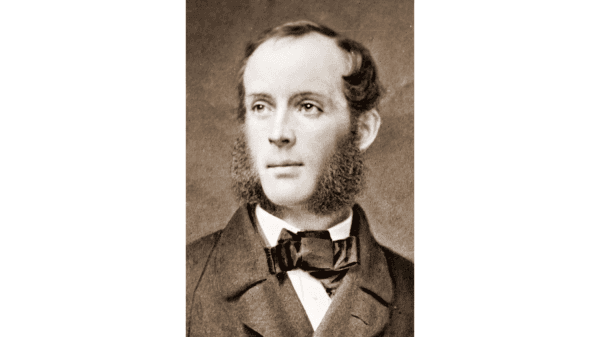

Like other landscape artists of the Hudson River School, Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) painted wild scenes of the new land: an American wilderness that most people had never seen for themselves. Church worked with such attention to detail that his paintings mesmerized the society of his day.

A photographic portrait of Frederic Edwin Church, 1826, by Brady-Handy. Library of Congress. Public Domain