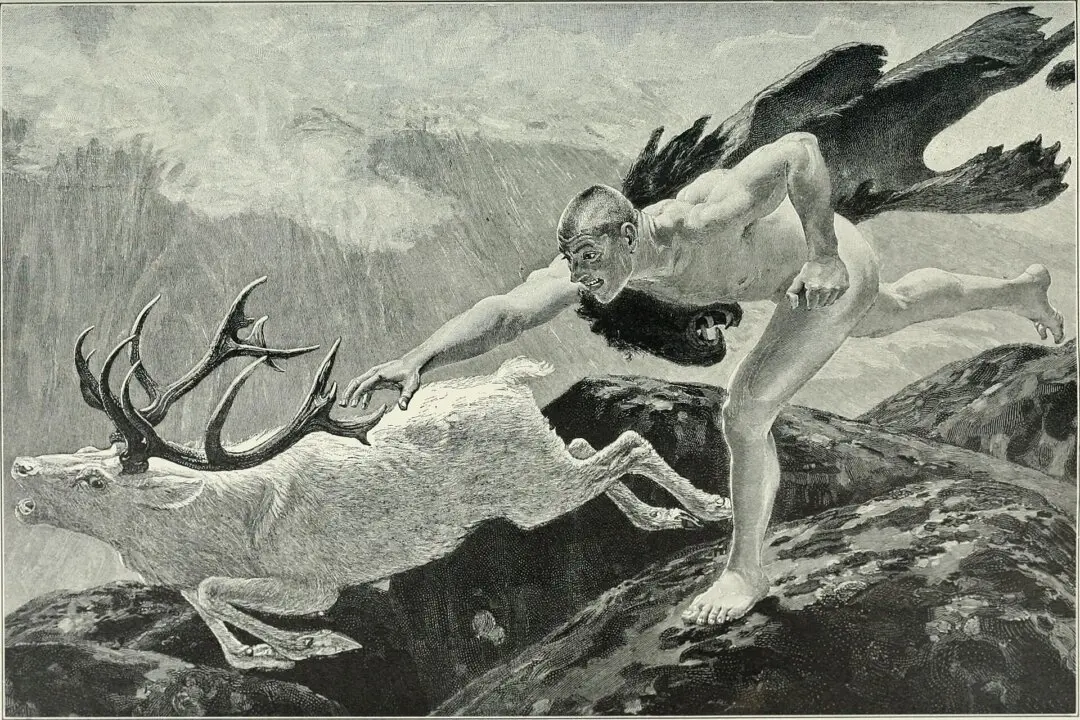

In modern psychology, we have books like “Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway,” which are international best-sellers and which focus on the idea that fear is the fundamental issue besetting human nature. The fear response clouds our judgment in so many areas of our lives, and when it does, we abandon our rationality, that is, our being Homo sapiens—wise, rational creatures.

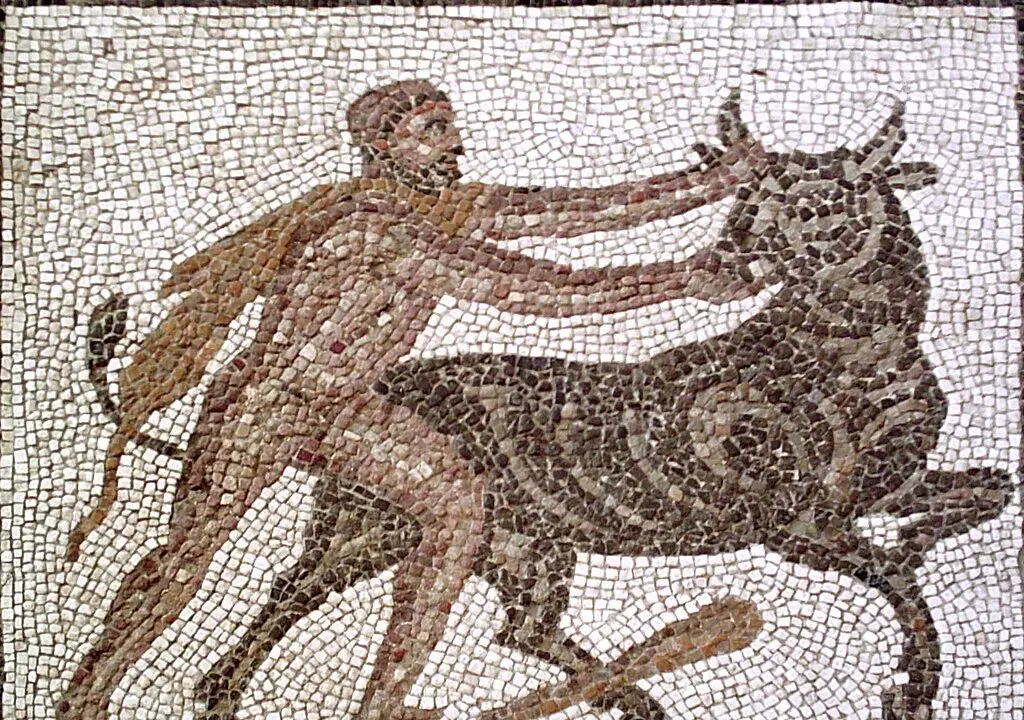

On his journeys, Odysseus has encountered Sloth (the Lotus-Eaters), Lust (the Cyclops), and Gluttony (the Aeolians)—three of the so-called seven deadly sins. But as we remarked in our first article in this series, the Enneagram includes nine deadly sins. And now on his voyage, Odysseus encounters one of the two extra sins that are not included in the typical list of seven: the sin of Fear.