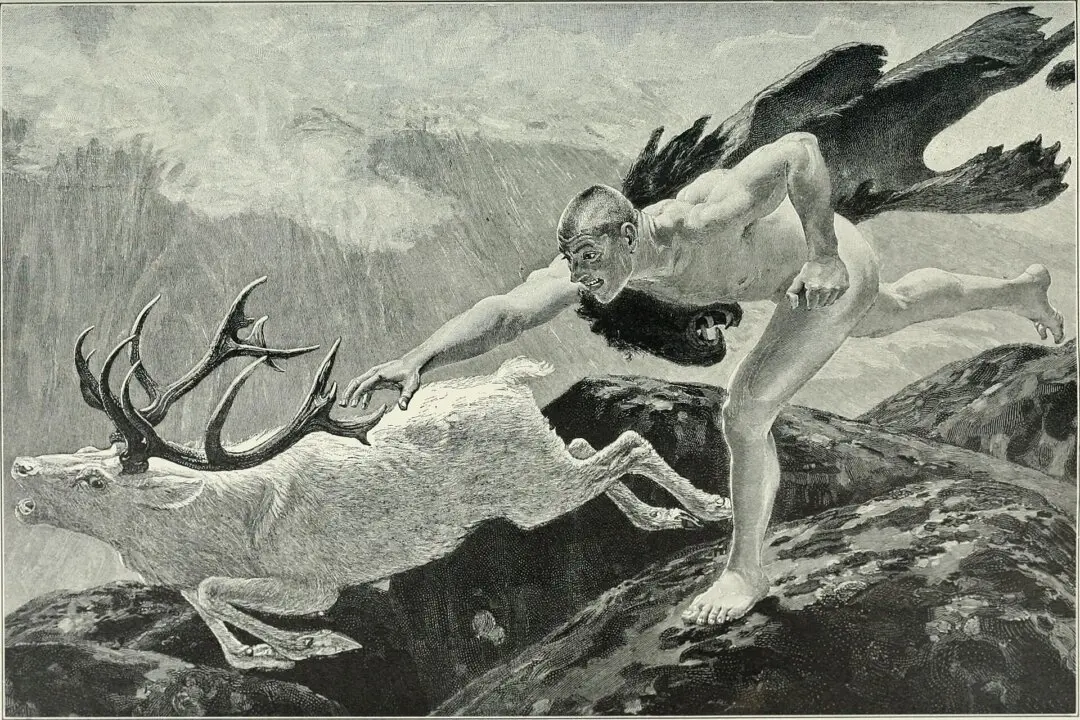

Finally, Odysseus comes to the last of the nine temptations of the soul as represented in the Nine Enneagram Types of personality. After the storms of the ocean raised by Poseidon in anger against Odysseus, Athene, the goddess of wisdom, beats the “breakers flat,” and from being “quite lost,” he arrives on the third day (surely, a resurrection for him) on the island of the Phaeacians.

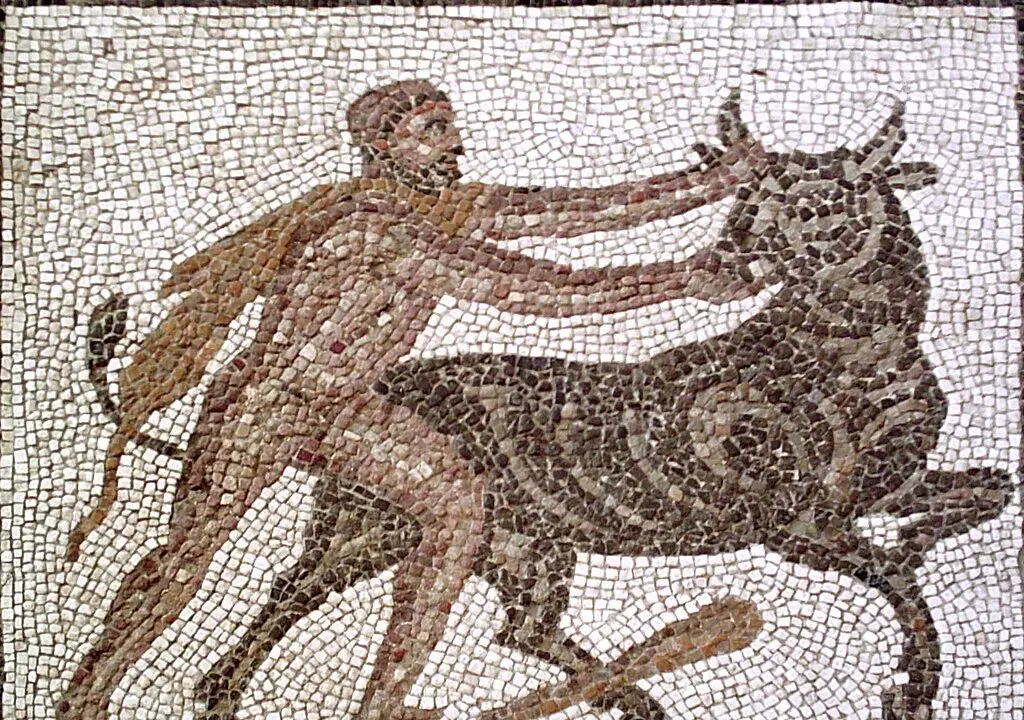

At this point, we need to understand that he is a very different man from the one who set out from Troy nearly 10 years earlier. He has endured and overcome—with divine assistance—eight deadly sins that had almost wholly destroyed him: sloth (Type Nine), lust (Eight), gluttony (Seven), fear (Six), avarice (Five), envy (Four), deceit (Three), and latterly with Calypso, pride (Two).