Fabien dei Franchi

To My Friend Henry Irving

The silent room, the heavy creeping shade,

The dead that travel fast, the opening door,

The murdered brother rising through the floor,

The ghost’s white fingers on thy shoulders laid,

And then the lonely duel in the glade,

The broken swords, the stifled scream, the gore,

Thy grand revengeful eyes when all is o’er,—

These things are well enough,—but thou wert made

For more august creation! frenzied Lear

Should at thy bidding wander on the heath

With the shrill fool to mock him, Romeo

For thee should lure his love, and desperate fear

Pluck Richard’s recreant dagger from its sheath—

Thou trumpet set for Shakespeare’s lips to blow!

In this sonnet Oscar Wilde addresses his friend, the Victorian actor Sir Henry Irving, cautioning him not to waste his talent on mere trash, but to devote himself to the art of great tragedy.

The title comes from the now long-forgotten melodrama, “The Corsican Brothers,” in which Irving played the twin brothers Fabien and Lucien Dei Franchi. The plot goes something like this: Lucien gets bumped off by a rival in love, but later reappears to his brother, demanding justice from the grave. Fabien swears revenge, tracks the murderer down and kills him in a duel. The end.

Initially, we thrill to Wilde’s descriptions of “the silent room,” “the dead that travel fast,” and “the opening door.” It all sounds like rip-roaring fun, although as the list goes on it turns into an avalanche of cliché.

“The murdered brother rising through the floor?” Ridiculous! The gothic tone becomes satirical, so by the time we get to “the stifled scream,” it’s difficult not to stifle our laughter.

(As an aside, there is a twist to these lines that Wilde could not have foreseen. The “ghost’s white fingers,” “the gore,” the “revengeful eyes.” Who does this remind us of today? In a word: Dracula. Indeed, it is believed that Bram Stoker, who worked as Irving’s secretary, drew on the actor’s tyrannical personality in his portrayal of the Transylvanian count. Perhaps all great actors are vampires as they strive to hypnotize our attention.)

Back to the poem: At the apex of the drama, as Irving’s eyes gleam with triumph, the tone abruptly changes. As if clicking his fingers, and bringing us out of a trance, Wilde declares, “These things are well enough,” but advises his friend to invest in “more august creation.”

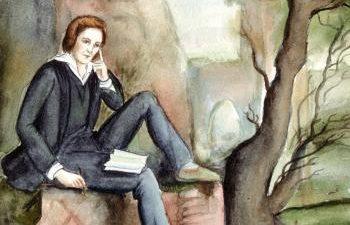

He should aspire to the very best. Wilde’s voice assumes a suitable gravitas as he summons forth a triptych of Shakespeare’s characters in little dabs of verbal color.

Who do we see first? King Lear: the great patriarch driven from his kingdom and reduced to raging fury on the heath as his Fool, amid the lashing rain, offers up Zen-like maxims to humble his pride.

Next, Romeo makes his entrance: the great lover, pining for Juliet beneath her balcony, while proving the swashbuckling hero in the streets.

Finally, Richard III: the great villain and evil hunchback, drawing his “recreant” or cowardly dagger to rend another victim and finally gain the longed-for English crown. King, lover, and fiend: three immortal archetypes of human experience.

What distinguishes “King Lear” from “The Corsican Brothers,” or from the average Hollywood film or TV soap opera? Wilde’s poem provides a clue.

Notice, how, in the first eight lines, there are no names, no people, only stock situations. In the last six lines, Shakespeare’s dramatis personae strut onto the stage, bringing with them the enormous psychological complexity that is so lacking from Fabien Dei Franchi or his modern equivalents, like Jason Bourne. We move from the stereotypical to what really makes us tick.

The poem’s final image sums it all up: Irving’s lips are the instrument through which pours the overwhelming musical tempest of Shakespeare’s genius. Nothing annoys me more than to hear his pounding soliloquies reduced to a tasteful murmur.

Shakespeare’s language is not, and never was, tasteful. It is lush, purple, and explosive—designed to keep the unruly hordes at the Globe Theatre from pelting the poor players with rotten onions. An honest ham, for me, does more justice to that vision than an actor delivering his lines with exquisite diction, but with all passion spent.

But what about our lips? When we recite Wilde’s poem, or Lear, or Romeo, or Richard III, it is not enough that we say the words aloud. We must put our heart and soul into them.

We need to pace the room and throw our arms around a bit! In so doing, something miraculous happens. We find that words, so drab, dated, and difficult on the page, become brilliantly alive.

That’s why it’s worth making the effort to read classic poetry. Unlike the vacuous entertainment we deaden our minds with, it breathes life back into us, like the trumpet blast that blows on the final day.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was an Irish playwright, novelist, poet, and author of short stories. He is most famous for his play “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Christopher Nield is a poet living in London. You can reach him at [email protected].

To My Friend Henry Irving

The silent room, the heavy creeping shade,

The dead that travel fast, the opening door,

The murdered brother rising through the floor,

The ghost’s white fingers on thy shoulders laid,

And then the lonely duel in the glade,

The broken swords, the stifled scream, the gore,

Thy grand revengeful eyes when all is o’er,—

These things are well enough,—but thou wert made

For more august creation! frenzied Lear

Should at thy bidding wander on the heath

With the shrill fool to mock him, Romeo

For thee should lure his love, and desperate fear

Pluck Richard’s recreant dagger from its sheath—

Thou trumpet set for Shakespeare’s lips to blow!

In this sonnet Oscar Wilde addresses his friend, the Victorian actor Sir Henry Irving, cautioning him not to waste his talent on mere trash, but to devote himself to the art of great tragedy.

The title comes from the now long-forgotten melodrama, “The Corsican Brothers,” in which Irving played the twin brothers Fabien and Lucien Dei Franchi. The plot goes something like this: Lucien gets bumped off by a rival in love, but later reappears to his brother, demanding justice from the grave. Fabien swears revenge, tracks the murderer down and kills him in a duel. The end.

Initially, we thrill to Wilde’s descriptions of “the silent room,” “the dead that travel fast,” and “the opening door.” It all sounds like rip-roaring fun, although as the list goes on it turns into an avalanche of cliché.

“The murdered brother rising through the floor?” Ridiculous! The gothic tone becomes satirical, so by the time we get to “the stifled scream,” it’s difficult not to stifle our laughter.

(As an aside, there is a twist to these lines that Wilde could not have foreseen. The “ghost’s white fingers,” “the gore,” the “revengeful eyes.” Who does this remind us of today? In a word: Dracula. Indeed, it is believed that Bram Stoker, who worked as Irving’s secretary, drew on the actor’s tyrannical personality in his portrayal of the Transylvanian count. Perhaps all great actors are vampires as they strive to hypnotize our attention.)

Back to the poem: At the apex of the drama, as Irving’s eyes gleam with triumph, the tone abruptly changes. As if clicking his fingers, and bringing us out of a trance, Wilde declares, “These things are well enough,” but advises his friend to invest in “more august creation.”

He should aspire to the very best. Wilde’s voice assumes a suitable gravitas as he summons forth a triptych of Shakespeare’s characters in little dabs of verbal color.

Who do we see first? King Lear: the great patriarch driven from his kingdom and reduced to raging fury on the heath as his Fool, amid the lashing rain, offers up Zen-like maxims to humble his pride.

Next, Romeo makes his entrance: the great lover, pining for Juliet beneath her balcony, while proving the swashbuckling hero in the streets.

Finally, Richard III: the great villain and evil hunchback, drawing his “recreant” or cowardly dagger to rend another victim and finally gain the longed-for English crown. King, lover, and fiend: three immortal archetypes of human experience.

What distinguishes “King Lear” from “The Corsican Brothers,” or from the average Hollywood film or TV soap opera? Wilde’s poem provides a clue.

Notice, how, in the first eight lines, there are no names, no people, only stock situations. In the last six lines, Shakespeare’s dramatis personae strut onto the stage, bringing with them the enormous psychological complexity that is so lacking from Fabien Dei Franchi or his modern equivalents, like Jason Bourne. We move from the stereotypical to what really makes us tick.

The poem’s final image sums it all up: Irving’s lips are the instrument through which pours the overwhelming musical tempest of Shakespeare’s genius. Nothing annoys me more than to hear his pounding soliloquies reduced to a tasteful murmur.

Shakespeare’s language is not, and never was, tasteful. It is lush, purple, and explosive—designed to keep the unruly hordes at the Globe Theatre from pelting the poor players with rotten onions. An honest ham, for me, does more justice to that vision than an actor delivering his lines with exquisite diction, but with all passion spent.

But what about our lips? When we recite Wilde’s poem, or Lear, or Romeo, or Richard III, it is not enough that we say the words aloud. We must put our heart and soul into them.

We need to pace the room and throw our arms around a bit! In so doing, something miraculous happens. We find that words, so drab, dated, and difficult on the page, become brilliantly alive.

That’s why it’s worth making the effort to read classic poetry. Unlike the vacuous entertainment we deaden our minds with, it breathes life back into us, like the trumpet blast that blows on the final day.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was an Irish playwright, novelist, poet, and author of short stories. He is most famous for his play “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Christopher Nield is a poet living in London. You can reach him at [email protected].