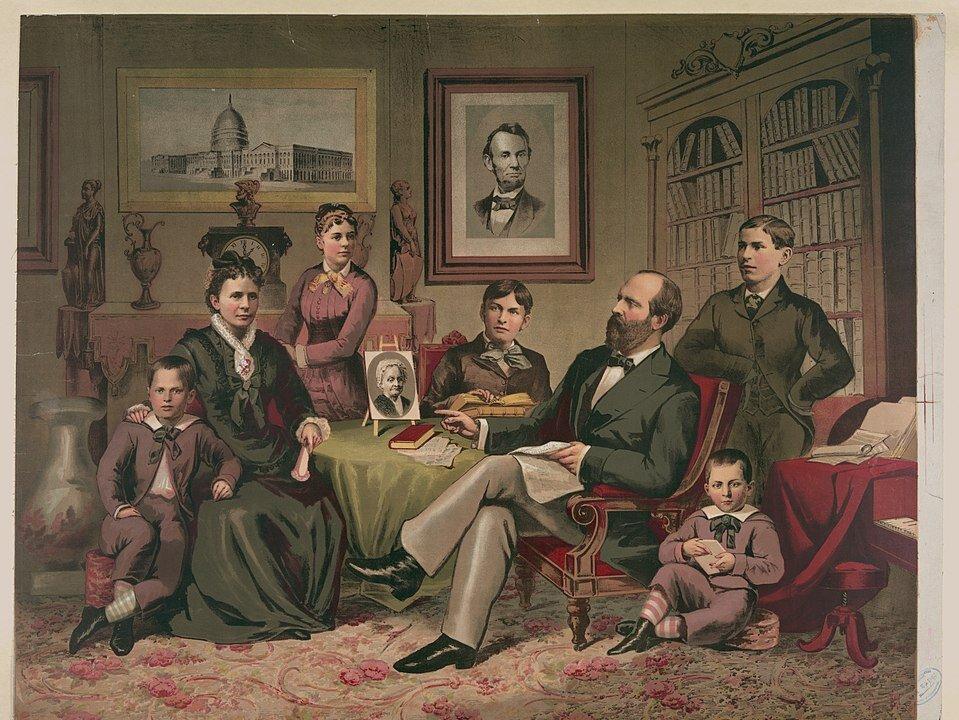

Over the course of 46 presidencies, four presidents have been assassinated while in office. One of these was James Garfield. However, instead of dying immediately or a day or so after the violent act, Garfield lingered for 80 days while a team of doctors tried to save him. During those hot summer days while her husband was mostly confined to a bed in a small room in the White House, first lady Lucretia Garfield nursed him, made decisions about his care, and parented their four sons and one daughter who ranged in age from 9 to 19.

Despite almost dying herself from malaria fever that started in May 1881, Lucretia handled James’s July 2 shooting, done by a mentally ill Charles Guiteau, with grit that undergirded a nation still shaky from the divisiveness of the Civil War. Although she believed that she paled in comparison to predecessor first ladies, the public “took pride in Lucretia’s courage,” according to the book “Destiny of the Republic” by Candace Millard. The book also shared that, at the time, The New York Times conveyed that “Mrs. Garfield has achieved a distinction grander and more lasting than ever before fell to the lot of a President’s wife.”