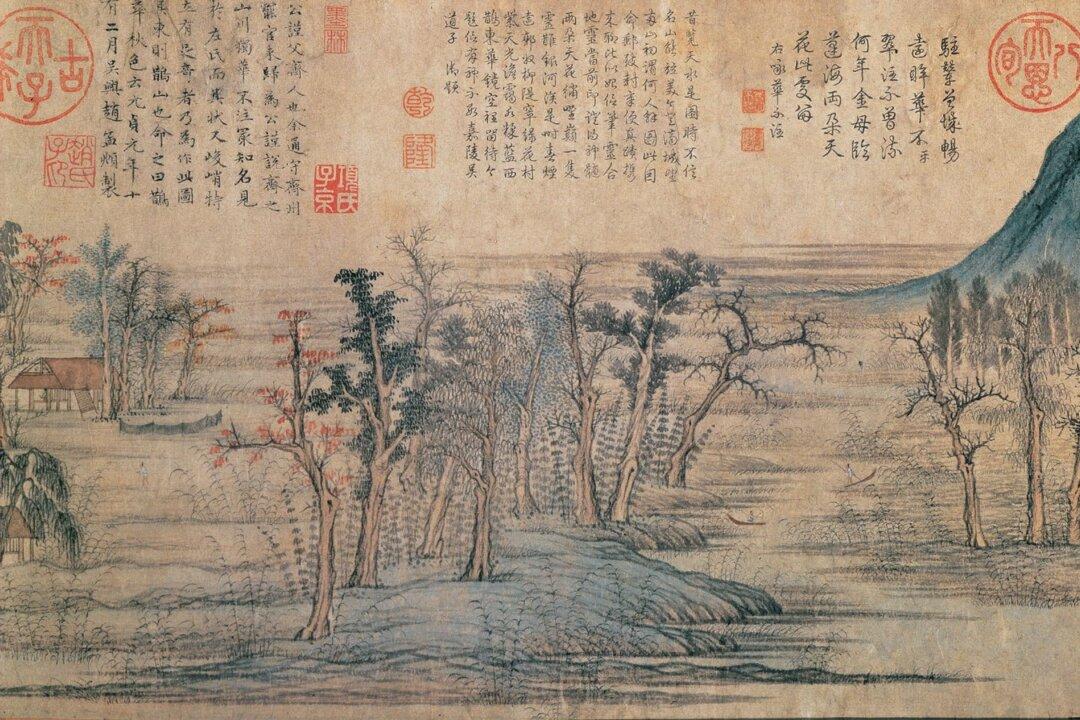

Stately mountains surrounded by flowing water—this is the essence of Chinese landscape painting, or “shan shui” (“mountain water”). Through its long development, the genre demonstrated the ancient Chinese belief that heaven and earth exist in harmony.

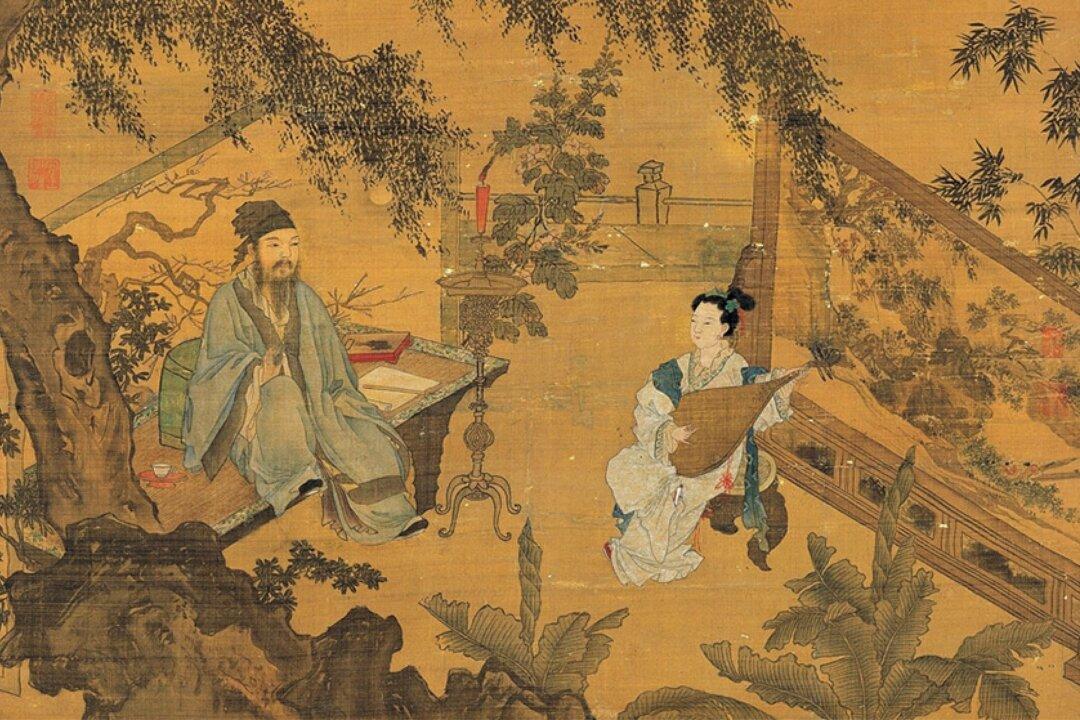

That ancient belief comes from Taoist philosophy which, in particular, influenced the art form: Tall, robust mountains reaching to the heavens represent yang, whereas soft, flowing water covering the earth represents yin. Situated together, these demonstrated the Taoist balance of yin and yang—essential in the design of the landscape painting. And against the backdrop of these magnificent forces of nature, humans were depicted as insignificant specks.