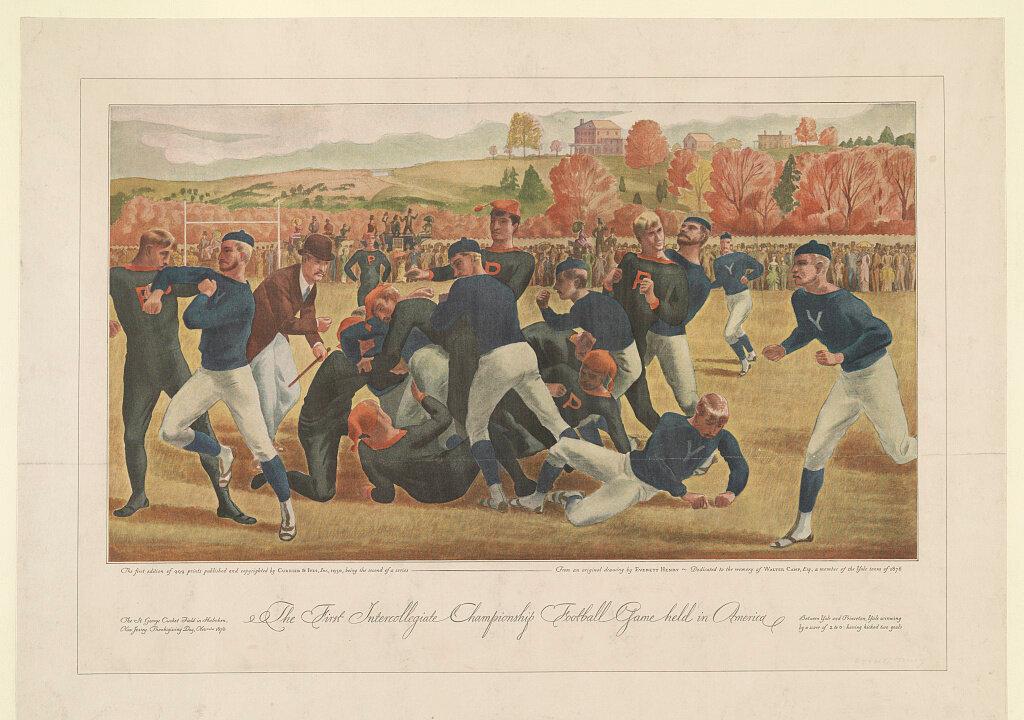

On Saturday, Nov. 13, 1875, an intercollegiate rugby match between Yale and Harvard was held at Hamilton Park, in New Haven, Connecticut. Among the game’s attendees was said to be a schoolboy named Walter Camp. He watched as both teams, each fielding 15 players, and each dressed in caps, breeches, jerseys, and stockings, scrummed and battled to an eventual Harvard victory.

One year later, Camp was a halfback on the Yale rugby squad and a few years afterward he was captain of the team. He soon became a part of the game’s rulemaking body—and forever changed the character of the popular sport.