Look I know it’s not a perfect show . . . but none of that matters . . . it does what a musical is supposed to do . . . it gives you a little tune to carry in your head . . . A little something to help you escape from the dreary horrors of the real world.

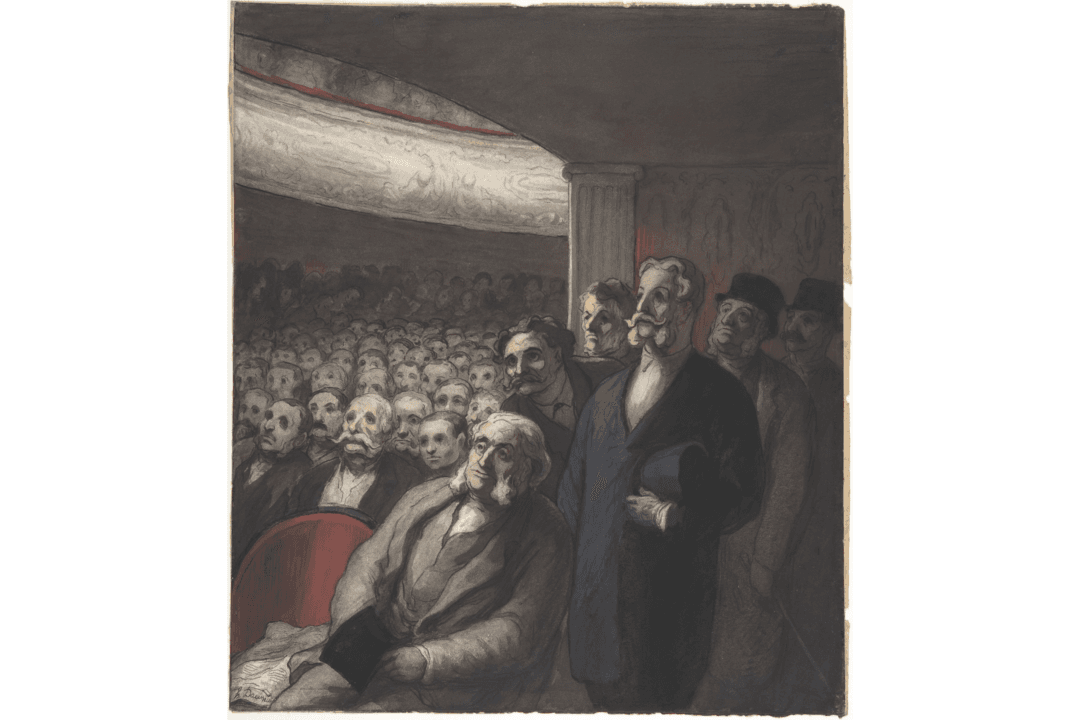

It’s been 15 or so years since these lines were spoken by the “Man in Chair” in “The Drowsy Chaperone.” Unfortunately, what struck me most upon seeing this otherwise fun and engaging musical were those final lines, particularly the bit about “the dreary horrors of the real world.” Is that true? Do we attend theater not simply to forget about our pedestrian trials and tribulations, but to evade a reality that is just too much to bear? In a world of “dreary horrors,” is there no hope?