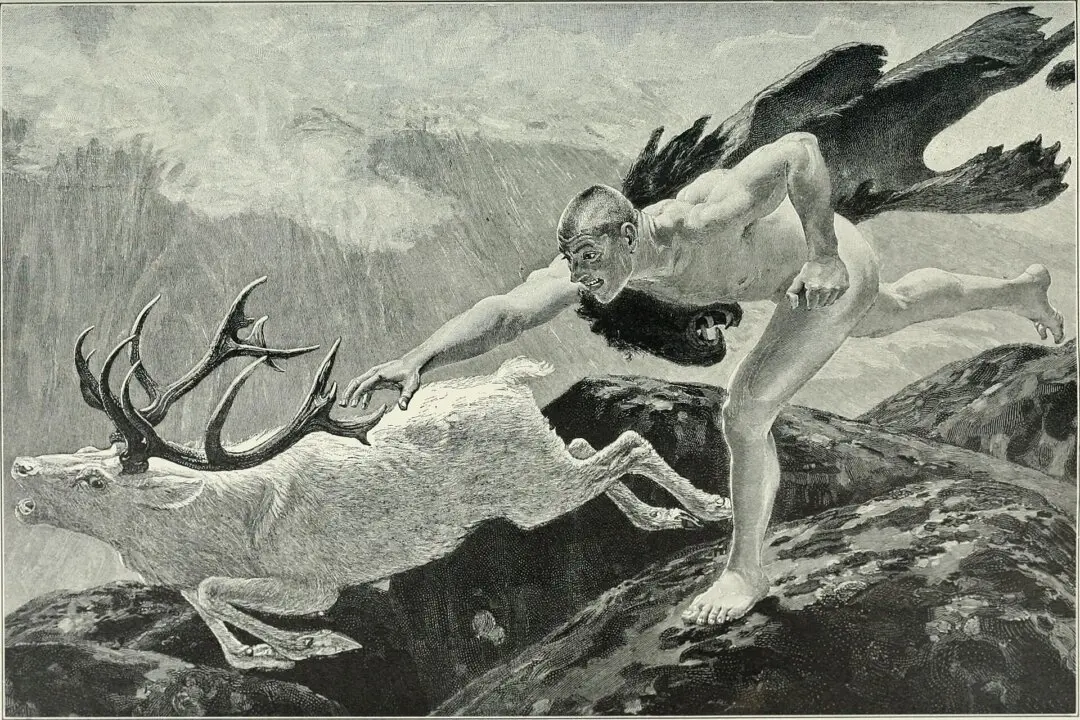

One of the most fascinating characters in the whole of Ancient Greek mythology is Prometheus.

I’ve written about gods and of heroes, but much less so of those beings who occupy a liminal space between gods and humans. Prometheus is neither a god, nor a human: He is a Titan, or more exactly, the son of a Titan. He’s one of the old order of beings whom the supreme god Zeus overthrew.