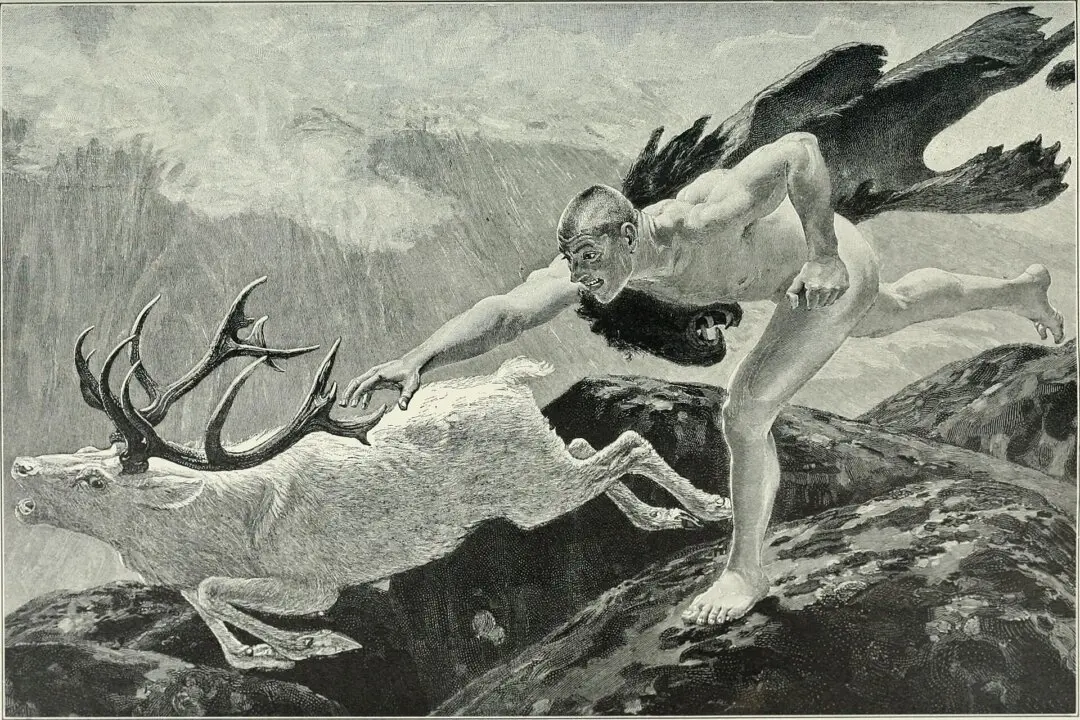

In Part 1 of this article, we looked at how Keats in his poem “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer” established a moment of pure sublimity in its final line; we looked at how he did this. The poem’s structure is a movement: from mentioning something very small, a book, to something much bigger, a peak in Darien, which seemed to represent the very height of thinking or of ego. But this peak was dwarfed in size by the next mention, the Pacific Ocean—the unconscious, perhaps—the enormity of which stilled the critical faculty into silence and left Cortez and his men, like us, stupefied in wonder. In other words, the poem left them and us experiencing the sublime.

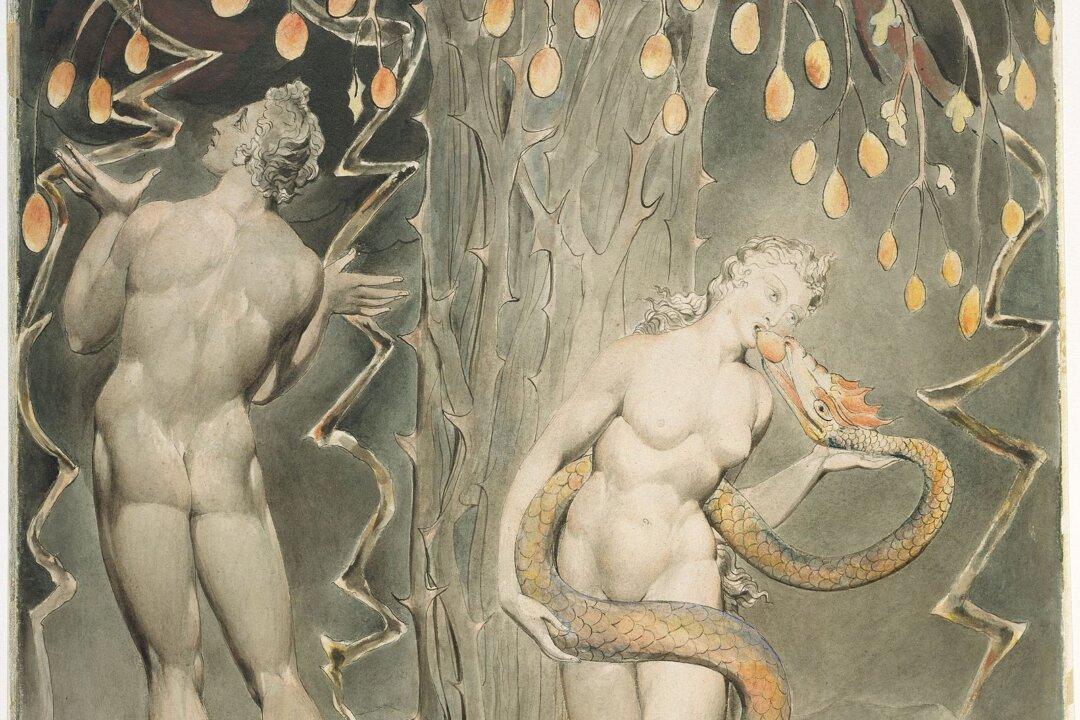

Keats is certainly a great poet, but now we come to one of the world’s greatest masters: John Milton and his “Paradise Lost.” Here, we don’t deal with sublimity in a line or two, but in huge stretches or chunks of writing in which the sublime is consistently maintained. So, I hope you will want to read the whole excerpt for yourself (“Paradise Lost,” book 4, lines 774–1012), and this can easily be found online. I shall, I hope judiciously, select some choice excerpts from this passage to make my points.