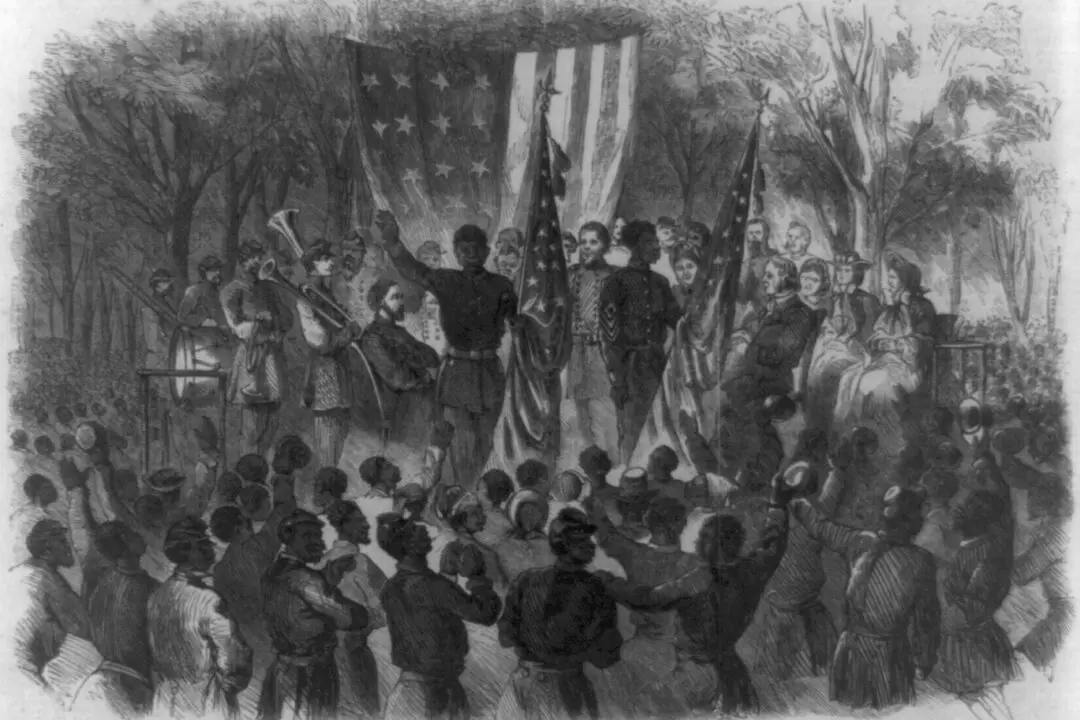

Born as a free African American in the 1830s, Louden Langley spent most of his life fighting for the government’s equal treatment of everyone.

Langley was well-educated, and he quickly adopted abolitionist views like his parents, Almira and William Langley, who churned butter and herded sheep in Hinesburg, Vermont. In the years before the Civil War, Langley’s parents would often open up their homes to those fleeing slavery via the Underground Railroad.