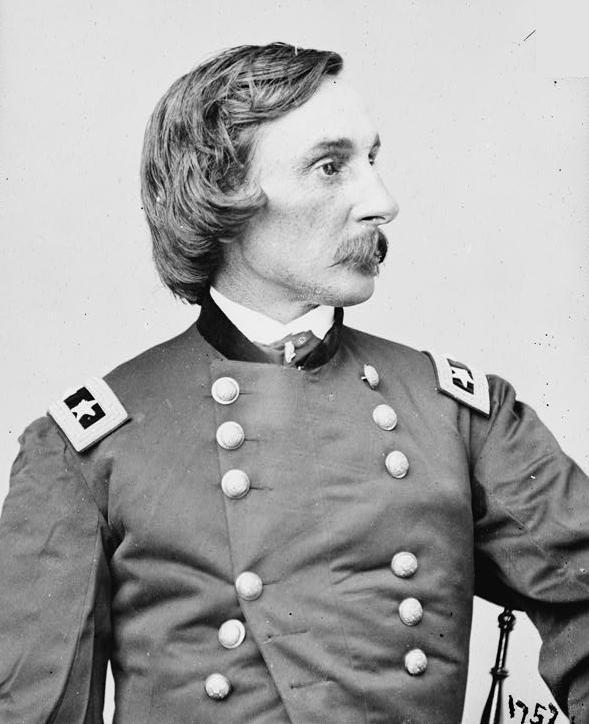

Gouverneur Kemble Warren possessed a keen eye for topography. His leadership in exploring expeditions during America’s westward expansion provided a precise vision of the open west. His eye for terrain would also serve him impeccably during the Civil War’s most crucial battle. Despite his accomplishments, a single injustice marred his name.

Mapping His Career

Gouverneur Kemble Warren (1830–82) was born in the small town of Cold Spring, New York, approximately 15 miles north of West Point along the Hudson River. At the age of 16, Warren received a commission to attend the Military Academy at West Point and exactly four years later, on July 1, 1850, he graduated second out of a class of 44. He would become the most accomplished of that class.

Gouverneur Kemble Warren was a mapmaking mastermind and capable Union general of the Civil War. Public Domain