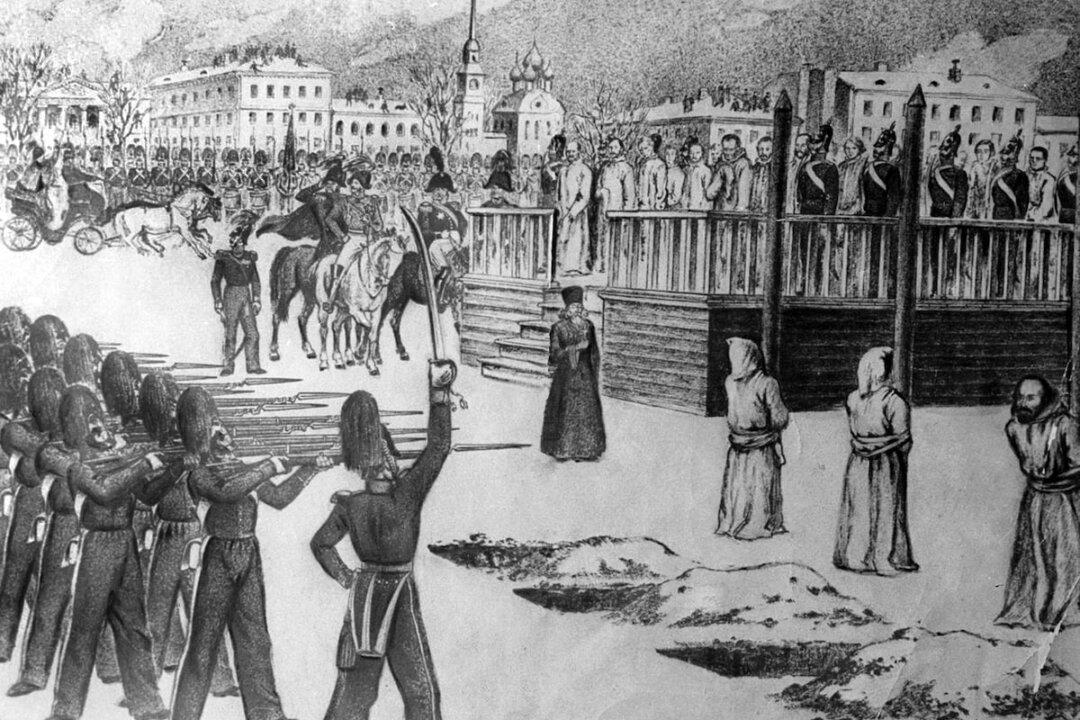

The firing squad leveled their weapons at the prisoners, who stood motionless, as though frozen, like the crystallized Russian winter landscape. Moments before, the prisoners had been made to put on the white shirts of condemned men, and told to kiss the Cross. Then they were tied to a pillar in the Semyonov drill ground, three at a time.

It was the end. What thoughts must have flashed through the prisoners’ minds in that all-consuming moment? One of the men, Fyodor Dostoevsky, in a letter to his brother, gives us a glimpse into the workings of his mind when, as he believed, his life was about to slip away.