Opera costumes are likely the second reason fans love the art form. Fabulous singing is why they happily purchase the ticket, but opera is an art that includes many art forms: orchestral music, ballet, and stunningly painted and beautifully crafted sets. It has something for everyone. Right up there in second place is costuming; it can range from fabulous to shocking and everything in between.

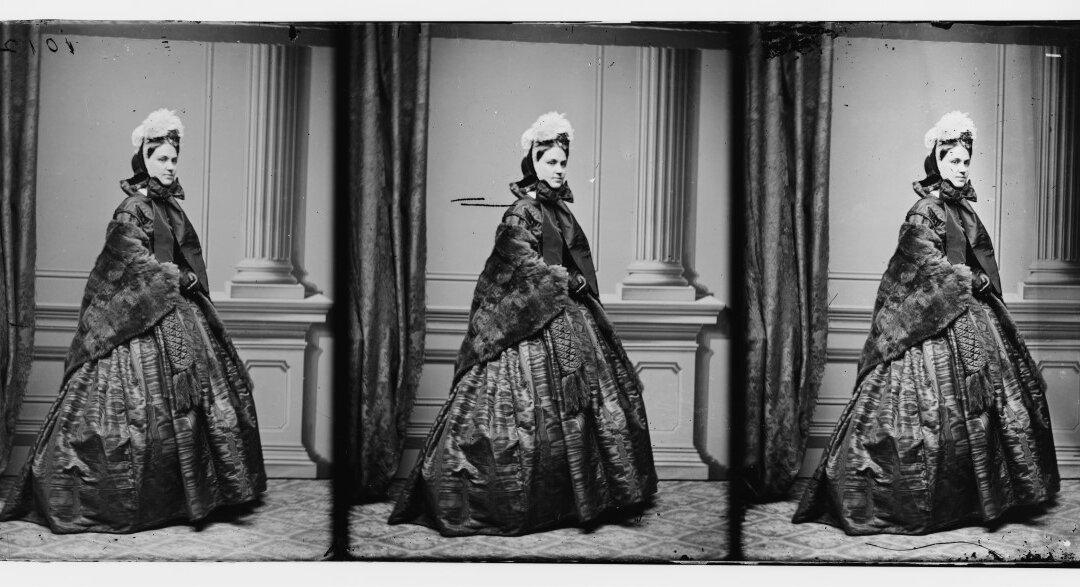

Costumes run the gamut from the ridiculous to the sublime. To begin with the sublime, the successful, late-1800s soprano Emma Abbott understood the power of beautiful costumes. “The costumes purchased during the summer of ’90 by Miss Abbott were not only the most elegant and costly ever bought by her, but exceeded both in cost and beauty any ever seen on any stage,” said author Sadie E. Martin in “The Life and Professional Career of Emma Abbott.”