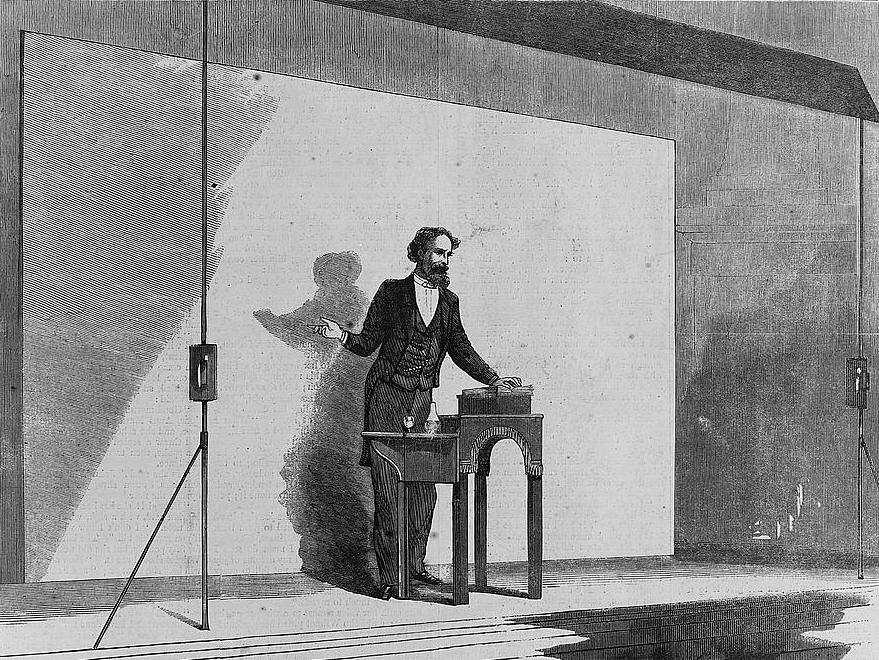

After nearly three weeks sailing the Atlantic Ocean, Charles Dickens arrived in Boston on Jan. 22, 1842. Still in his 20s, Dickens was one of the most famous people in the world, let alone most famous authors. By the time of his arrival, he had published five novels in six years: “The Pickwick Papers” (1837), “Oliver Twist” (1838), “The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby” (1839), “The Old Curiosity Shop” (1841), and “Barnaby Rudge” (1841).

When the famous British author arrived, he was met by a throng of fans, journalists, and curious onlookers. He, along with his wife Catherine, had come to America to visit the new republic and learn how it was, if it was at all, different from his home country. Although he had not come to sell his books, he had in mind the notion to defend his books, and authors’ rights in general.