Religion and salvation no longer preoccupy the modern Western world. Now, we focus on personal development and “self-actualization.” We see this idea played out in a thousand ways. But what does it mean?

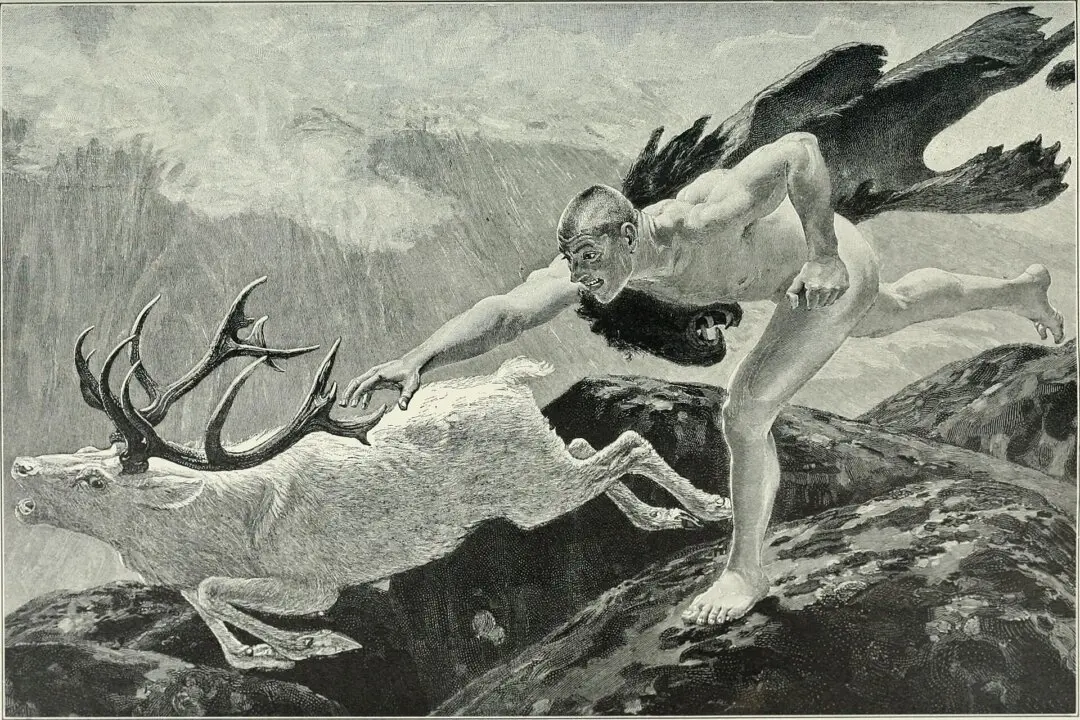

One thing that the neglect of religion and salvation means is connected to the oft-repeated mantra “You only live once.” It implies that we need to enjoy or fulfill ourselves now. The clear implication is that we must ensure we drain every last drop of juice out of life and not miss out on anything that life has to offer before we go. This is why we hear more and more about bucket lists. It’s become a moral lapse—if not an actual crime—not to have ticked off everything on our “bucket list.” So get busy!