Bernard Baruch (1870–1965) was born in Camden, South Carolina, but when his father, Simon, decided to move the family to New York City, the decision not only altered the trajectory of Bernard’s life, but also greatly influenced the trajectory of the nation during the early to mid-20th century.

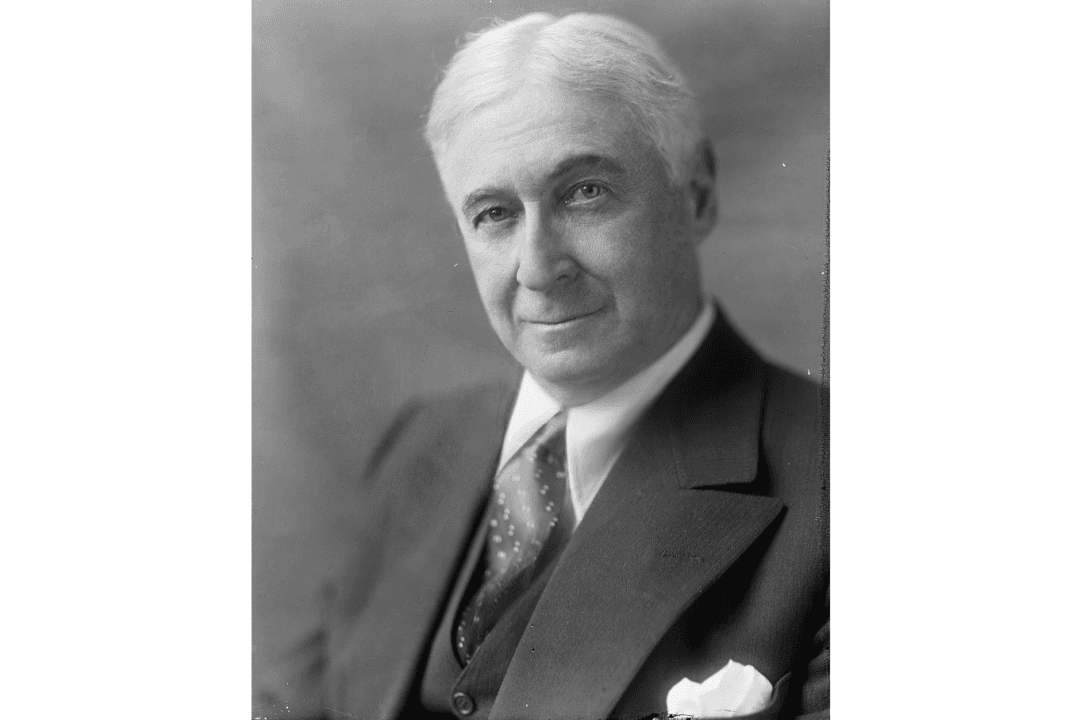

Simon Baruch, father of Bernard, was a field surgeon during the Civil War. Public Domain