Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no! it is an ever-fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand‘ring bark, Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken. Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle’s compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me prov’d, I never writ, nor no man ever lov'd.

Among Shakespeare’s most famous and enduring sonnets, we find this gem, “Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments.” In these 14 lines of iambic pentameter, Shakespeare offers profound reflections on the true nature of love, particularly in its relation to time and change.

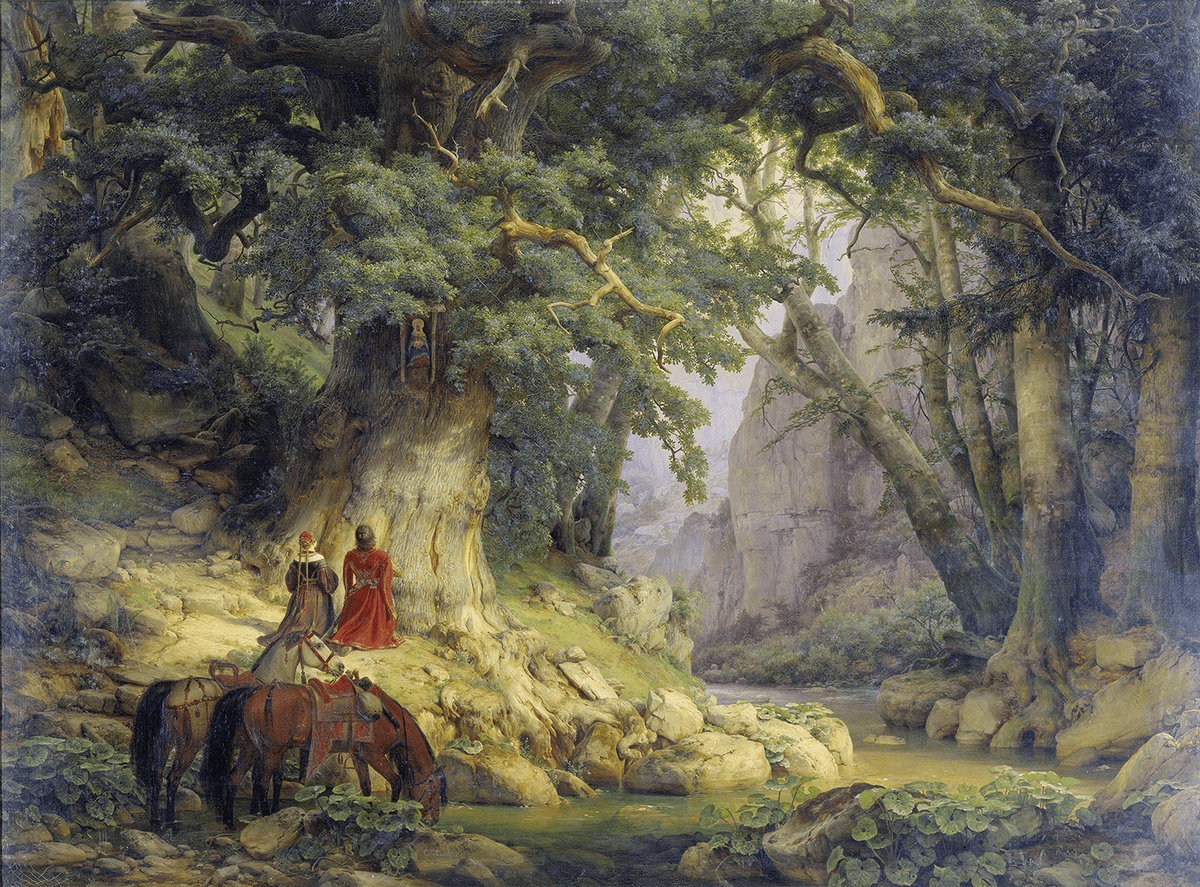

A married couple kneels at a shrine in front of an ancient oak tree, the symbol of endurance and eternity. "The Thousand-Year-Old Oak," 1837, by Karl Friedrich Lessing. Oil on canvas. Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany. Public Domain